This Asian American Life: An Interview with Michelle Kuo by Evelyn Nien-Ming Ch’ien

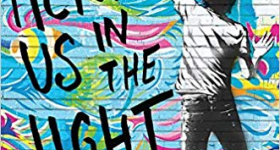

Michelle Kuo Skyped with me from her apartment in Paris. She’s now teaching law at the American University of Paris and navigating her way through French traditions and culture after graduating from Harvard Law School and working as a civil rights lawyer in California. Her book, Reading with Patrick (Random House, 2017), is a memoir about her year teaching in the Mississippi Delta and befriending one of her students, Patrick, who was incarcerated for murder a year later. Deferring her own life’s plans, Michelle returned to read for seven months with Patrick while he was in jail. Her riveting narrative has been embraced globally for its compassionate message, its exploration of education and its insightful glimpse into societal inequality.

EC: Who’s the audience for your book?

MK: In the back of my mind, one audience is Asian Americans because we just don't have stories about where we fit into the black-white discourse. We don't feel permission to talk about our position on race because we're made to feel ashamed of the idea that we have privilege or the idea that we’re the model minority. We don't see stories about how hard it is for Asian Americans to pursue social justice because it's viewed as such a risk to our immigrant parents; we should be filial [and] that that's a valid concept. Then the other reader, I think, is the elite liberal of any race who is really self-congratulatory about their beliefs without having that kind of humility that we need as a country. That lack revealed itself especially after the election. There was this giant mea culpa: we know nothing about rural areas, there's a huge divide between rural and urban, between poor and rich.

EC: Can you talk about the writing process at all?

MK: At first I didn’t want to write because I didn’t feel it was my story to tell. Because it was an unequal relationship, because I’m Asian American and don’t feel permission to write about race and poverty, because I wasn’t from this place and I wondered what a person from Helena, AR would say.

So, the not wanting to write became part of the ambivalence of the book, and I think what makes it so complex is not having easy answers. But I did write because sometimes there are stories we have to tell — especially in this political climate where there’s so much pessimism about interracial relationships, about "doing good.”

Like some people recommend, I wrote in short bursts, just a little bit — 25 minutes— in the early morning, and the theory is that the rest of the day your subconscious could bloom with ideas. You’re picking up things and thinking about it even when you’re not sitting at the desk, and your mind craves returning the next morning.

EC: Certainly, Asian Americans have a specific set of complexities as sociological subjects and cultural expectations are entrenched. For example, a white person bonding with a disadvantaged minority is a cliché or the basis for a miniseries. An Asian American woman in a position of power doing this is unfamiliar territory. How did it feel to be completely honest about that?

MK: It’s funny we feel so different from white people. I think many of us do, but it's been funny sometimes. For example, when I’m randomly reading some review on Goodreads — which my husband has now banned me from reading — it will say, “This is a white savior story, except she's Asian” and I'm thinking wow, some people really do think that Asian means white.

But there is a history of white philanthropists, of white people who come down during the civil rights movement to integrate. The poor and Asian person has a totally different history and meaning. It was hard for me to write it because I didn't know what my tradition was. My parents didn't talk to me about Taiwan, which didn't democratize until after they left. I inherited their silences in a way that I still don't understand. I didn't grow up with many traditions, white savior or otherwise.

I feel like Asian Americans are really generous because we're constantly seeing ourselves in other stories—we don't have a choice, as there aren't many stories about us. I did see myself in both the African Americans from Arkansas and Mississippi who are involved in civil rights struggles. I saw myself in all of these texts even if there weren't any Asians in it. When I talk to Asian American readers of the book, we're all connected by the void, by recognition of a void of stories. That's a weird way to be connected, and it's not intuitive.

EC: Yes, most immigrants are focused on trying to just survive so the void is created from that; just trying to survive, many Asian families simply couldn't afford to make those connections. Asians can be very isolated as immigrants. Was anyone else involved in Teach for America from your graduating class at Harvard?

MK: Yes. I mean, it's interesting. Teach for America has changed a lot. When I was an undergrad, a lot of people were doing it at Harvard. I always assumed people were motivated by the desire to do good. But I talked to this Princeton undergrad who was in the Delta. She was teaching at a public school in Mississippi, which has a dire teacher shortage and is the poorest state in America. She was telling me that when she told her fellow students this was her duty for America, like they would call her on the phone and say, "You're a good person; how could you be doing this?" Like there was an active attempt by other students to stop her from going to Mississippi to be a teacher, right? It’s important to go to Mississippi and analyze how it operates on the ground. It’s clear that some elite kids read critiques of neoliberalism and then apply them to a fellow student's desire to go to a place only a few venture into.

How different is that from the 1960s in which we gave the benefit of the doubt to thousands of college students from elite universities who went to the South to desegregate even though they were outsiders, even though they were privileged. It's really fascinating to me, when we're talking about trends, how there's such a trend to be destructively suspicious of service. I think there's like a whole secular discomfort with service. Other cultures like Latino communities feel really comfortable with service because they come from a more religious tradition. They understand that when you do service professions like teaching, mental health, counseling, you become foot soldiers in a larger battle.

EC: Yes. But I also think that Asians have an interesting niche in many cities. We're not considered a service group even though Asians do so much service in places like San Francisco, with organ donor organizations, law centers, immigration centers and other social programs. Moreover, Asian Americans provide affordable and alternative medical practices and even reasonably priced groceries. There's no pretension about it, either.

MK: I think you’re absolutely right that there’s less pretension about doing good in Asian American culture.

When I was talking to my parents about my life choices in my 20s, my mom got so frustrated with my language, and I used to get pushy with her, but now I see that she was totally right. She said, “Stop bragging to people that you do work that is nonprofit. They don't want to hear that. They're going to think you think you're better than them.” You know, the Chinese were initially brought to the South to supplement sharecropper labor and they refused to do it. When they got here, they started creating their own grocery stores all across the Delta. Some of them are still there, but many have left. That's really interesting to me too, just their role in selling goods to black families and then also being allowed to hang out with whites but not always being allowed to attend their schools.

EC: Can you tell me about Helena and the Delta?

MK: People are friendlier. They are nicer. They do smile more. I'm a terrible driver, fulfilling all Asian stereotypes, and I like it. Nobody ever honked at me when I was just spaced out in front of a green light. People are just really, polite in a way. I think some of that politeness is, as anywhere, hiding stuff, but I liked it. There are a lot of amazing things about living in a rural area, but of course, it's just more poor. There are just fewer sources of fresh food.

EC: Do you still keep up with Patrick?

MK: Yes I do. I just saw him last week when I was back in Arkansas, which is really nice. It’s not the same as living somewhere like you were saying earlier. There’s a difference between coming and going and living somewhere. I was worried that when I was writing the book that I was being melodramatic about leaving. And now I think, no, maybe I wasn't dramatic enough. The decision to stay in a place is a decision to keep strong, deep relationships. They’re just really hard to maintain whether it's a spouse or a student.

Comments