When I visited my family in San Diego during Chinese New Year, I thought news of my recent divorce would be the main focus of the holiday event. I was wrong.

My Chinese parents had a substantially harder time digesting the news that I had become vegan.

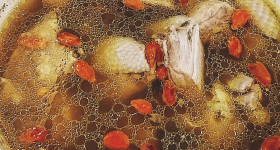

Chinese New Year features an annual migration of the Chinese from metropolitan dwellings to countryside homes. Families and friends gather around lazy Susans to gorge on symbolic dishes such as steamed whole fish, rice cakes and homemade dumplings. The meal signifies abundance in a literal way. The thought process: the more dishes you prepare, the more food you consume, the better off the coming year will be.

When I announced to my Shanghainese parents that I had become vegan, a sense of deep confusion overcame them.

“Are you getting enough nutrients? How will you have energy with only vegetables and fruits? You must eat meat!” they protested. While these claims may seem hyperbolic, my parents take them very literally.

They were deeply offended.

I anticipated their questions regarding my diet, yet I did not realize the tenor that my dietary choice would strike. My rejection towards the more nutritionally dense foods, such as meat and seafood, seemed almost dismissive to my parent’s generation, who experienced no accessibility to resources. My parents were born into a couple of bourgeois families in Shanghai in the ’40s. They grew up eating the most exquisite of meals; xiao long bao and shi zi tou (lion’s head meatballs) were merely appetizers.

However, access to food for many Chinese people quickly became restricted when the Great Famine swept across the country from 1959 to 1961. Then Mao Zedong led the Cultural Revolution, a decade-long sociopolitical reform that tortured millions of people, paralyzed the education system, destroyed economic development and imprinted a collective trauma that many have not, and will likely never, recover from.

Even after the Great Famine, meat supply was limited during the Cultural Revolution. What we think of as basic foods now were all rationed back then. Families and kids would wait in line for hours for pantry staples such as rice, oil, flour, sugar, salt and eggs. Meat, especially red meat, was a luxury. While there was a monthly ration for meat, the stores usually didn’t have them in stock. If your family got lucky, the meat would be prepared in the most economical way to extend the shelf life just a little bit.

An expansive landscape prompts an expansive mind. To explore more of my parents’ disapproval of my veganism, I took my mom to the Torrey Pines cliffs close to where they live in San Diego and asked her to tell me stories of her experience during the Cultural Revolution. I looked at the smooth creases on my mother’s face while she recollected the morning when the Red Guards invaded her home in Shanghai. I was familiar with these facial wrinkles; I grew up observing them. The nasolabial folds down her cheeks were my favorite — they would deepen to push my mother’s childlike cheeks upwards when she was happy. As my mother went on with the story, rare creases showed up; they were crowding on her forehead and between her eyebrows. These lines softened as if they were afraid to be seen.

That day, the Red Guards stripped the three-story townhouse down to nothing, driving away three trucks full of antiques, family heirlooms and everyday necessities. Then they proclaimed liberation to the working class and ordered the three live-in maids to take anything they wanted from the home and leave the family. The maids were brought up by my mother’s family and were an extension of the family. In fear of being labeled anti-revolutionaries, they took several cooking pans while tears streamed down their faces. My mother, along with her parents and seven siblings, were separated by the Red Guards by gender into two bedrooms and detained. The room my mother was in didn't even have a blanket left in it for the frigid winter of Shanghai. My mother, along with her 12-year-old sister, heard pleading cries through the frosted windows. At first, the cry was episodic and sharp, then it turned to sounds of defeat and depletion. Later, my mother learned that the neighbors were tortured to death by the Red Guards. As the cries faded into silence, a Red Guard member took my mom to the kitchen, where half a dozen of the rest of the Red Guards stood impatiently. He instructed my mom to make tea for the group. She obliged, poured water into a pot, turned on the stove and walked away. “Where are you going?” a Red Guard asked. “I’m not going to wait around while the water is boiling — I’m going back to the room,” my mother said dispassionately. Furious, the Red Guards imprisoned her at her school for a week. “I am from a bourgeois family,” she was forced to write. “My bourgeois family is against the socialist system. Therefore, I am from a bad family.” She wrote these sentences repeatedly for three days.

My mother gazed at the paragliders soaring above the cliffs. “How beautiful,” she remarked, after telling me her story.

“That must have been so hard for you and your family. How did you feel?” I asked.

“Well, it was hard,” she replied. “We went from being an elite family to having nothing. My family was considered to be from a bad background.”

My question became irrelevant as the brainwashing from the past plunged her into a cold blast of psychological detachment. “Can you tell me how you felt? I imagine it must have been excruciating emotionally,” I nudged. I looked for signs of emotions on her face. Like the moment before terror envelops a child who realizies that she has lost her parents, her eyes fixated on the horizon, her face drew a blank. And that was when I realized history has disabled not just her, but generations.

For my parents, me coming out as vegan excavated a graveyard of trauma in China from the ’70s. It dug up the jarring herd mentality enabled by an extreme regime, the bitter, salty sweat from hard labor reform in lieu of higher education, the shrewd thrust that violated ethics and morale and basic human rights.

Back then, death by starvation was as common as the flu. And now we kill ourselves through gluttony. To my parents, my becoming vegan was a timestamp of the contemporary mindlessness. They hoped that I would never taste hunger like they had, when they, along with their families and friends, had bodies that deflated, ached and suffered from hunger, not knowing when it would end.

Last night, while texting my mom, she gave me a verbal lesson on the best way to make Shanghainese spring rolls for Chinese New Year.

“Shiitake mushrooms. Napa cabbage. Bamboo shoots. Ginger. Wood ear mushrooms. Julienne everything, thin and even. Stir-fry in a wok. Put a little soy sauce. Add a dash of huangjiu. Stir and toss. Stir and toss. Add a little cornstarch slurry. Toss, toss and toss. Let the filling cool down completely. And then wrap them up in spring roll wrappers. Don’t be greedy and overfill them. Otherwise, they will burst,” she wrote.

She had left out what used to be a vital ingredient: pork.

This is perhaps as direct as a Chinese mom like mine will be to show acceptance. I smiled and hurriedly typed up the recipe.

Comments