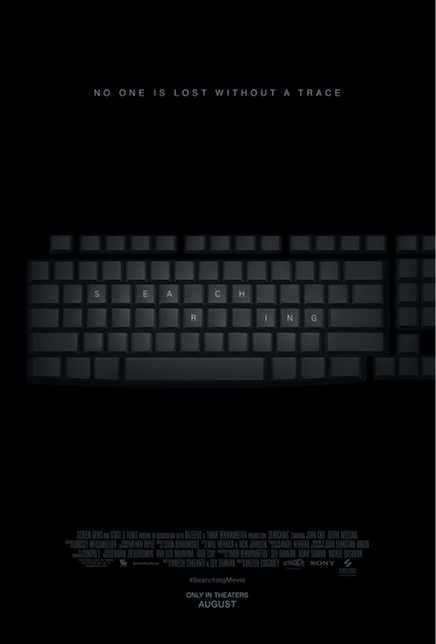

Searching, the new movie starring John Cho, is a first-of-its-kind thriller. Told entirely through computer screens (think iMessage texts, internet browsers featuring Gmail and Facebook, Facetime calls), the plot follows David Kim (played by Cho), a suburban dad searching for his teenage daughter (played by newcomer Michelle La). As he frantically uncovers clues through her email and social media, he begins to understand he doesn’t know his daughter very well at all.

The film received rave reviews at Sundance and received a wide release in late August. Since then, viewers have commented on everything from the innovative way the film was shot, hidden easter eggs, and the fact that — finally! — there was a movie #starringjohncho!

I called first-time director Aneesh Chaganty while he was on set in Canada to chat about its tear-inducing opening, the technological aspect of the film and, of course, his thoughts on where Searching fits into the Asian American film canon, if at all.

(This interview has been edited for clarity.)

Hyphen: The opening of the movie feels like a mashup of the first 10 minutes of Up and those great, poignant Google ads that came out several years ago. I know you left your former job directing commercials at Google to work on this. Did your time there help inspire the concept for the movie?

Hyphen: The opening of the movie feels like a mashup of the first 10 minutes of Up and those great, poignant Google ads that came out several years ago. I know you left your former job directing commercials at Google to work on this. Did your time there help inspire the concept for the movie?

Aneesh Chaganty: You know, we were pitching this from the beginning as Up meets the Google commercial. It’s funny, so many people have said to us, “I don’t want this to be offensive but [the opening] reminds me of Up,” and I’m like, “Yo, that’s the least offensive thing on the planet; Up is one of the greatest films of all time.”

As far as the Google commercials go — yeah, I spent two years writing, developing, directing Google commercials. My bosses were those people whose work you’re probably referring to — “Dear Sophie,” “Parisian Love” — two commercials that opened my eyes to what storytelling could be outside of these traditional parameters. I learned so much about how to emote something on the screen, how to emote the cursor over the blinking bar or a button being pushed. The opening of the movie to me is the commercial part. It has the pace of a commercial, it has the feel of a commercial and it brings out emotions very quickly like a Google commercial. Looking back on it, all of that time at Google was this weird training ground, not only to make the whole movie but specifically that particular opening sequence is very informed by that time and our multiple Up viewings.

Hyphen: I don’t know if this was purposeful or not, but when I was watching the movie, I had this very meta moment where I thought, I’m watching a screen on a screen. I think it adds to the tension but is also somewhat fatiguing, which made me think about how much technology both connects us and distances us. Primarily it’s a thriller, being told in this really creative way, but I’m wondering if there was a specific messaging behind the ways technology is both an aid and a handcuff in some ways.

AC: Yeah, I think so much of the way media portrays technology is exclusively negative, you know, whether it’s a Black Mirror episode or Facebook PSA. It’s always about how stuff is going to ruin our lives and how it alienates us and disconnects us and while that is true, that’s not the whole pie. I think what we wanted to do in this film was do something we felt no film had done before, which is zoom out and show more of the pie. Which is that yes, tech does have some of the power to alienate us, disconnect us and make us stare at our phones all the time, but just as much as it has the power to do that, it has the power to connect us and make us love and laugh and feel. I think that aspect of technology has not been touched upon in any Black Mirror episode or media that we’re used to. It’s often portrayed as a reason that things happen horribly. In our movie, it’s just a fact of life, and as a fact of life, it has good sides and bad sides. Someone pointed out something really interesting recently: where any other movie could have said, “Margot goes missing because she had Instagram,” in our movie she goes missing and she has Instagram.

Hyphen: And she’s found because of Instagram, actually.

AC: Yeah, in a lot of ways. The tech is both the heart of the problem and the root of the solution.

Tech does have some of the power to alienate us, disconnect us and make us stare at our phones all the time, but just as much as it has the power to do that, it has the power to connect us and make us love and laugh and feel.

Hyphen: So I heard that you had always only considered John Cho for this role. What’s striking to me is that this story could easily be told with an actor of any ethnicity. So why did you envision John particularly for this role?

AC: So there’s two answers to that. There’s why John Cho and why did we want to cast an Asian American in this role. I’ll start with the John Cho part of it: John Cho because he’s a movie star, because he’s amazing and he’s the guy that literally everyone watches and goes, “Oh I love that guy.” I don’t know anyone who walks out of his work and thinks, “I don’t like that guy.” Everybody likes him, everybody wants him to be in more stuff, he just isn’t in more stuff. So we thought, “Oh, this is his opportunity, we have to put him in this thing, he’s incredible.”

We wanted to cast an Asian American family specifically for a bunch of reasons as well. Number one: personally, I grew up in Northern California, in San Jose, where this takes place. I wanted to cast a family at the heart of this that looked like the families that were my neighbors, that came over for dinner, who my parents worked with, who looked like they lived in the place we grew up in. Growing up, watching my favorite films, those films never had people that looked like me in them. And I’m not talking about films like Monsoon Wedding or Slumdog Millionaire that had to cast people like me because they were about race and culture. I’m talking about the spy movies, Mission Impossible, Bourne Supremacy, like the movies that I loved watching, these thrillers, films that had nothing to do with race and culture — in those films, casting people that looked different than the norm was something that never happened. To me, here was an opportunity for us to do that, for us to be like, “Let’s give this opportunity to a different group of people.”

The other benefit of John Cho, going back to that is, in addition to being a movie star, he’s anchoring the family here. John, right now — and hopefully this won’t be the case forever — he’s one of the few recognizable Asian American leads in Hollywood, as far as someone people can say, “Oh yeah, that person has been in stuff that has made money” or “That person is bankable enough,” or is financially not too big of a risk for a big company to take. You always have to think about what big money is going to think about all of these things. John Cho has precedent. But the beauty of casting John Cho in a dad role is that he’s able to anchor the movie as this being a “John Cho movie” and around him we’re able to introduce a bunch of unknown talent, talent that doesn’t need those big movies in parentheses. Now because of this film, those actors will have this movie in parentheses and hopefully they can feed that movie down the line and be an anchor to other people. What I learned about this whole process was that if you take one person to anchor these other people and if you bring the movie up to a certain level of quality and people like it, all of the newer talent will now see the effects of it. So John was not only a big win for us because he is amazing and fits the Asian American mold, which is something we wanted to do regardless, but also because he allowed us to do something more cool, which is bring in new talent. Because that’s the focus the industry doesn’t have. It doesn’t have more than a few faces, and we need more than a few faces in order to be more representative of the world we live in.

Hyphen: Totally, I think it gave such a great platform for these other actors, and that’s really appreciated. Something else that is interesting is, like I said, you could totally swap out the characters’ race, and the story would be the same story in a lot of ways. And yet at the same time I think having them be a Korean American family adds on an extra layer because you end up viewing the film with a different lens. I’ve read in some other interviews you’ve done that you don’t necessarily consider this to be an Asian American film, but that it’s a film with Asian Americans, unlike, say, Crazy Rich Asians (which I’m sure you’re getting mentioned in the same breath as a lot recently). It’s distinct from tackling issues of race. But both films deal with family and love and how much or little we understand those we love. So I’m curious as to what you think is the distinction that makes one film an Asian American film and one that just features Asian American actors?

Hyphen: Totally, I think it gave such a great platform for these other actors, and that’s really appreciated. Something else that is interesting is, like I said, you could totally swap out the characters’ race, and the story would be the same story in a lot of ways. And yet at the same time I think having them be a Korean American family adds on an extra layer because you end up viewing the film with a different lens. I’ve read in some other interviews you’ve done that you don’t necessarily consider this to be an Asian American film, but that it’s a film with Asian Americans, unlike, say, Crazy Rich Asians (which I’m sure you’re getting mentioned in the same breath as a lot recently). It’s distinct from tackling issues of race. But both films deal with family and love and how much or little we understand those we love. So I’m curious as to what you think is the distinction that makes one film an Asian American film and one that just features Asian American actors?

AC: That’s a good question. I think what you’re citing is an NPR podcast in which John and I were asked the same question, and at the exact same time one of us said, “Yes” and the other said, “No.” John called this an Asian American movie and I called it not an Asian American movie, and the funny thing is we gave those answers for the exact same reasons.

To me, it’s my goal: I don’t see Mission Impossible — I don’t see these spy films, these action films, these thrillers, these mysteries, these mainstream movies — I don’t call them white movies. I call them movies. They’re just movies. What I call Indian stories, what I call Asian American stories are films like The Namesake. Films that deal with culture to me are films that should have that cultural element when you describe it, as an Asian American film or Indian American film. But this film isn’t that. This film is a movie about an American family. It only has become described as an Asian American film purely for the fact that this doesn’t happen often. If this movie was made 20 years from now, in a world that I’m positive will be dominated by a lot more representative media, nobody would call this an Asian American film. And what I’m hoping is that in 10 years, people will look back on the so-called progressiveness of our movie and think, “What exactly was it doing that was so special?” You know, we did nothing that was special; we literally just cast the family that traditionally doesn’t appear in movies, that’s it. To me that doesn’t justify [the label of] an Asian American film, it just justifies a movie that is more representative of the world that we live in. It’s only Asian American because this is the first time an Asian American has led a thriller, which is crazy to me — that in 2018 that we are the first movie to ever do that. I think we have become part of this conversation because we are the first, but I don’t think we deserve to be in this conversation. Just because we are the first doesn’t mean this is where it needs to end up. Because where it needs to end up is to a point where this is not an issue, where this is not a film that is heralded for anything apart from just being unconventional and a thriller. That is why I don’t call this an Asian American film, although I do recognize the rarity and the value of the messaging that we’re putting out to larger Hollywood by casting a family that is Asian American and saying it doesn’t matter. That’s our point here, that it doesn’t matter who the cast is, it is the story that will propel it and anybody will show up. You don’t have to have the same faces all the time.

What I’m hoping is that in 10 years, people will look back on the so-called progressiveness of our movie and think, “What exactly was it doing that was so special?”

Hyphen: Yeah, I understand that. I think there’s an interesting conversation about the definitions of [Asian American films]. Though I do agree that hopefully, in the future, we don’t think these stories are special in their rarity.

AC: If I’m describing Crazy Rich Asians — and I’m only saying this because we’re always in conversation with them now — in this description, you have to say, “A Chinese American woman is dating a Singaporean boy who takes her home to meet his family.” You don’t have to say that with our movie. You don’t have to say “a Korean American family.” “A Korean American father loses his Korean American daughter.” You can say “a dad loses his kid.” And that to me is what makes a movie an Asian American or cultural movie, is that you have to say it to explain the plot, and you don’t have to say ours to explain the plot.

Hyphen: I guess some would argue that the fact that it is being created by and features Asian Americans, that by itself is a definition of — you know, that they’re not mutually exclusive, that something can be both just a film but also be an Asian American film.

AC: Yeah absolutely, that’s a very valid argument. And again I’m 27 years old, made a movie two years ago, and we never ever thought we would be part of this conversation, so I’m just kind of observing what people are saying around me. But at the end of the day, I think the thing we are most proud of is that we are able to take five other unknowns and put them into industry and have a presence. That is an objective win; that needs to happen. Whether or not this is an Asian American film or not is almost moot next to the point that we are going to have more faces soon [in Hollywood] looking like everyone.

Comments