One of my favorite essays of 2020 was Elizabeth Miki Brina's "Missing Ghosts," published in The Sun. I'm thrilled that our February 2021 nonfiction is an excerpt from her much anticipated memoir, "Speak, Okinawa," the story of growing up in upstate New York as the child of an Okinawan woman and an American soldier.

Available for purchase here or wherever books are sold.

-Grace Jahng Lee, Creative Nonfiction Editor

I

WORSE THAN THE DOG

I asked my dad why all the great stories were sad ones. “Most good stories are mysteries,” he said. “The author is like a detective trying to get to the bottom of some truth, and happiness is a mystery that can come apart in your hands when you try to unravel it. Sadness, on the other hand, is infinitely more resilient. Scrutiny only adds to its depths and weight.”

—Bliss Broyard, “My Father’s Daughter”

My first memory: a dog bites me, on the arm, not hard, but just enough to jar me into consciousness. His name is Shiro, which means “white” or “castle” or “generation” in Japanese, depending on how it is written. Shiro has long white hair, blue eyes and a grayish-pink nose. I am 3 years old and he is just above my height, but I can still look him in the eyes. I believe we understand each other, our arrangement. I believe, at age 3, I’ve earned his subservience. He carries himself proudly. Majestic, like a horse.

So one day, when no one else is around, in the backyard, beside the cinderblock fence, as he lowers his head to drink from a shiny porcelain bowl of water, I try to mount him. He growls and bites me. He doesn’t frighten me. He embarrasses me, shames me. And as a small child, an only child, accustomed to endless doting, I wouldn’t tolerate these strange emotions. I cry and run to my mother. I don’t tell her why I’m crying. I’m afraid that if I tell her she’ll scold me worse than the dog did.

Shiro is not to be ridden like a horse.

Shiro was my obaasan’s dog. Obaa, my grandmother, my mother’s mother, found Shiro when he was still a puppy, eyes closed, curled up into a ball, quivering on a pile of garbage.

Often at night, Obaa pushed a cart through the streets of Kadena, a town located on the island of Okinawa, where my mother was born and raised, where I lived for six months when I was 3 years old. Often at night, when the air thinned and cooled, when the sounds of jets, helicopters and gunfire coming from the nearby military bases quieted, Obaa pushed a cart through the streets and rummaged through trash heaps, searching for cans and bottles to sell, scraps of wood and metal to reuse. She lived in a house with a rusted tin roof, a rusted tin gate, a floor raised from the mud by cinder blocks, with a single room for cooking, eating, drinking, sleeping and playing cards, a backyard for bathing and growing sweet potatoes, which she ate for every meal. She lived almost all her life in this house, the house where my mother grew up, the house my grandfather built after their previous house was destroyed during the battle.

.

The Battle of Okinawa. That is how most of us have heard of Okinawa. But as a battle fought and won, and quickly disregarded. Not as a battle on which our entire contemporary history depends, from which we are still recovering.

It began in April of 1945 and lasted 82 days. In Japanese, the battle is referred to as “tetsu no ame.” In English, the phrase means “rain of steel.” The Okinawans simply refer to it as Okinawa no Sensho, “Okinawan War.” Although a conquered nation for many centuries — first as a tributary of China, then as a colony of Japan — Okinawa had never known such carnage. For 82 days, thousands of planes dropped hundreds of thousands of bombs on the island, crushing and burning countless creatures, plants, houses and buildings. For 82 days, hundreds of thousands of troops invaded the island, wielding tanks and guns, throwing grenades and shooting into hiding places. One hundred forty thousand Okinawans, a third of the population, were killed. That does not account for all those who died of injury, illness, starvation after the battle. That does not account for all those who were forced to commit suicide. Of those killed, some were conscripted soldiers called Boeitai, boys as young as 12, ordered to fight in the front lines. Some were nurses or members of relief teams called Giyutai, girls as young as 14, ordered to cook and tend to the wounded. The rest were civilians. One hundred twenty thousand civilians. Who died in a war they didn’t choose, sacrificed to protect Japan, the precious mainland. Many Okinawans believe that those who died had died in vain. Or, rather, what they refer to as “a dog’s death,” inujini.

When news spread that Okinawa would soon be attacked, Obaa was living by herself with her four children, my mother’s older brother and older three sisters. My grandfather, conscripted four years earlier, was somewhere in Korea, being held prisoner. When the sirens blared, days before the troops landed, before the ships could be seen from shore, Obaa and her four children — her son, age 4, and her three daughters, ages 3, 5, and 7 — grabbed sacks of potatoes they had been gathering and storing for months. They hid in caves while the ground shook with each explosion, while their island, their home, crumbled and turned to ash. They fled from cave to cave, while their sacks emptied, while their clothes loosened and unraveled from their shrinking bodies. For two years after the war, they wandered from camp to camp, slept in tents or under tarps. They bathed in the ocean. They ate what they could scavenge. They collected rain and drew from low muddy wells for drinking. When my grandfather returned from Korea, he was a different person. He returned, but he was gone.

Somehow Obaa kept herself and her four children alive and unharmed through one of the most horrific battles in history. A story I wish she could have told me.

Yet these memories are impossible to forget, regardless of whether we actually lived through them. I believe they stay in our bodies. As sickness, as addiction, as poor posture or a tendency toward apology, as a deepened capacity for sadness or anger. As determination to survive, a relentless tempered optimism. I believe they are inherited, passed on to us like brown eyes or the shape of a nose.

.

I had not learned this history, my mother’s history, my history, until I was 34 years old. Which is to say that I grew up not knowing my mother or myself.

.

Three years after the war, my mother was born. She was born into poverty and chaos. She was born into a family, an entire people, stunned by violence and grief. When my mother was born, Okinawa was still considered an “enemy territory.” This meant that the occupying U.S. military was under no obligation to restore the battered landscape, and Okinawa was still a vast ruin of decay and rubble. This meant that the occupying U.S. military guarded and patrolled the wreckage of an island, and Okinawans relied on bare subsistence rations of bread and milk, cans of red chili, popcorn and candy. Some of the troops gave the prettiest girls bright new clothes to wear and called them “honeys.” Some of the troops broke into homes, robbed and raped Okinawans inside homes, because there were no laws against it, no laws at all.

In 1952, three years after my mother was born, around the age she would have formed her first memory, Japan officially relinquished rule of Okinawa to the United States. My mother witnessed the U.S. military devouring the island, constructing immense complexes of bases. She witnessed forests and fields, wetlands and beaches becoming concrete. She witnessed farmers and fishermen, carpenters and potters, cooks and shopkeepers becoming mere labor. Her brothers were hired to help build the bases. Her sisters were hired to serve food in the cafeterias. Obaa cleaned barracks. My grandfather also cleaned barracks, but mostly he just stayed in bed, too sick with grief, humiliation and alcoholism to do much of anything else.

For many years after the war, in order to supplement her income, Obaa cooked breakfast and lunch for a few of her neighbors; a couple of them were orphans, older than her youngest children, old enough to work, but still needing someone to care for them. She cooked on a portable gas stove while they drank tea and played cards in the same room. They paid her one dollar to sit on her floor and eat food she prepared. Not much, just potato and broth.

Not long after her own children moved out and moved away, after my grandfather gambled and drank himself to death, Obaa found Shiro on a pile of garbage and brought him to her home.

She held him like a baby and fed him with a bottle. Then he grew older and bigger, and they would sit together at the same table, which was already low to the floor, perfect for a dog, and share from the same bowl. One piece of potato for her, one piece for him. She would slurp some broth and give the rest to him. Back and forth. For every meal.

Shiro trotted beside her as Obaa pushed a cart through the streets.

Shiro was not to be ridden like a horse.

.

My first memory of Shiro biting me is all I remember of the time I lived in Okinawa. There are many photographs of my aunts and uncles holding me and smiling, my cousins holding me and smiling, Obaa carrying me on her back and smiling. We are not just posing for photographs. We are smiling because we are happy. I am a small child and I don’t know what sadness is yet, and therefore I make everyone happy.

There is a photograph of me at a beach, lying on my stomach on the sand, wearing a red-and-white polka-dotted swimsuit and sunglasses much too large for my face. I am laughing, probably because the person behind the camera is laughing.

There is a photograph of me in the park, standing on a pair of giant bronze statue boots, each boot bigger than my whole body, wearing braids and bow-shaped barrettes in my hair, arms crossed and brow furrowed, trying to look tough, probably because the person behind the camera is showing me how to look tough and I am mimicking her. We are having fun, pretending and playing together, because I am happy and everyone loves to play with me.

But I do not remember any of these moments. They are just photographs my mother had taken and framed, and hung on walls or put on shelves around the house. They do not belong to my life. They belong to hers.

What I do remember is walking through Newark Airport. I am walking with my mother, staying very close to her, holding her hand. A man walks beside us. He smiles a lot and wants to hold my hand, too, but I won’t let him. I won’t let him because I don’t know him. I don’t remember him because my first memory is of Shiro biting me. My mother tells me the man is my father. She tells me that he stayed behind, here, where we are now, in the United States. She tells me that he was traveling, looking for a better job and a better place for us to live. That is why we had to live with my aunt on Okinawa for six months. That is why we have returned. Because the man is my father and her husband. We belong with him. She says “Otosan … Otosan … Anata no otosan.” Father … Father … Your father. She tells me in Japanese, because back then I could understand and speak Japanese. I hold my mother’s hand tighter, hiding from him behind her.

And for a long time, that is the closest I ever felt to my mother. When I was still in her world.

.

What my mother and I share now is an understanding that precedes words. It is an understanding that comes from being the same body, being fed, bathed, clothed, held in her arms every day, loved every day, then becoming separate, growing apart, then remembering how much that hurt, remembering and being grateful for the distance we traversed, the distance we were able to recover. It is an understanding that comes from forgiveness.

My mother and I communicate through layered small-talk, subtexted chitchat, a shorthand that took years and years to develop, and satisfies our desire to be close.

But will that ever compensate for the years and years of silence, for the time we missed, the time I squandered?

***

My mother was born in 1948, three years after the war, three years after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. She was born and raised in Kadena, the sixth child of a fisherman and a fisherman’s wife, both from Miyako, one of the many smaller islands that surround Okinawa. I don’t know much about their lives before the war, because they were never able to tell me. They were never able to tell my mother. They worked hard with their bodies every day to feed themselves and their children, and when they didn’t work, they were too tired to talk to their children about such trifles as their lives when they were younger.

My mother quit school before she finished eighth grade. She worked for 50 cents an hour in a factory that manufactured bento boxes until she turned 16, old enough to work at a nightclub as a waitress. She worked as a waitress for the rest of her life, at nightclubs in Okinawa, then at Japanese restaurants in the United States. When she moved to the United States, she dreamed of climbing the social ladder to the status of secretary or accountant, of wearing pressed suits and blouses and typing reports, but disillusionment quickly settled. She couldn’t speak English. She couldn’t learn English fast enough, well enough. Working hard with her body was all she knew. Working hard with her body was her rightful place, and the restaurants became her retreat, a backdrop of wood-and-paper paneled screens, rock ponds filled with koi fish, the strumming of three-stringed guitars heard through stereo speakers, which so faintly reminded her of home. She always gave some of her paycheck to her mother and younger sister, even long after she left Okinawa. Sometimes she still gives some of it to her spoiled daughter.

.

According to Japanese legend, if you make a thousand paper cranes you are granted three wishes. My mother made a thousand paper cranes once, shortly after she became a waitress. Her three wishes were to marry an American, an American who would buy her a big house, and together they would have a child — a daughter, fingers crossed — who could eat as much as she pleased and sleep on a bed in her very own room.

.

My father was born in 1948, three years after Victory Day, three years after the Cold War commenced. He was born in Brooklyn and raised in Manhattan, the first child of a wealthy Italian immigrant and an English-Irish-Scots woman who could trace her lineage back to Jamestown. My grandfather salvaged a small portion of his family’s wealth despite the Great Depression. To prove his loyalty to his new country, he enlisted in the army and swiftly ascended the ranks as a translator. He could speak Italian, Spanish, French, German and English, fluently. He studied philosophy at Columbia University, then founded one of the first telephone-answering services in New York City. My grandmother was his receptionist. A recent graduate of Hunter College, 22 years old, 15 years younger than my grandfather, when they married. They bought a corner condo on the Upper West Side, where they raised three boys.

My father and his two younger brothers went to Loyola, a prestigious Jesuit high school at 88th Street and Park Avenue, not too far from where they lived. My father was taught Latin. He was taught St. Thomas Aquinas. He read every play by Shakespeare, every book by Dickens, Conrad, Hemingway and Fitzgerald, by the time he graduated from Fordham University, another Jesuit institution. After he enlisted in the army, following in the footsteps of his father, he read The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and The State and Revolution by Vladimir Lenin because he “sought to understand the mind of the enemy.” His exact words. My father became an Airborne Ranger, a Green Beret, then a captain. He fought in the Vietnam War. He fought to save the Vietnamese from communism, from tyranny. When he returned to the United States, he dreamed of keeping up the good fight, of solving the nation’s economic problems, but he couldn’t keep a job for very long. There was always a boss to rebuke, a partner to contend with, a devious consumer policy he refused to abide. There was always a layoff, a bankruptcy, a recession, persecution for being a veteran. Eventually, the narrative shifted, and the culprits included the Women’s Movement, Affirmative Action and the “Jews in charge of Wall Street.” I cringe to admit that’s what he believes, but that’s what he believes. Writing it feels like betrayal, because he is my father and he means so much more to me than his bigotry.

.

My father believes in the code of heroes, of men, of strong men who protect the weak. He believes in honor and sacrifice. If my mother or I asked for anything, needed anything, he would do anything. He wouldn’t sleep or eat, he wouldn’t stop fighting, wouldn’t surrender.

.

I was born in 1981, the year Ronald Reagan was inaugurated as the 40th president, the year MTV began broadcasting. I was born in Elk Grove, a suburb of Chicago, the first and only child of an aspiring entrepreneur and an expatriate. Around the time I was born, my father graduated from Northwestern University with an M.B.A. in operations management and my mother started taking ELL classes. My mother hated those classes, she confided years later, when I became old enough to care enough to ask her.

“Too hard. I want to stop going, but your father not let me. He make me study. He study with me. He help me.”

Good for him, I thought to myself. Not yet comprehending the unfairness, the very lopsided power dynamic. Not yet aware of the ease with which she conceived and uttered the word “let,” the ease with which I heard and processed it. We accepted the word without resistance, with a nod of approval.

We always listened to my father. We trusted him.

Because my father was the parent who knew what to say when I asked about thunder and lightning or jumping off a diving board, about the girls who teased me or the boys who ignored me. He knew what to say to teachers and gymnastics coaches. He knew what to say, and he said it so well. His pronunciation was perfect.

Why didn’t I learn Japanese? Why didn’t my father learn, and require me to learn, like he required my mother to learn English? Perhaps ethnocentrism is to blame. Perhaps learning a language that wasn’t European wasn’t very popular in the 1980s. Perhaps my father heeded what the psychologists were claiming at the time, that learning two or more languages at once would confuse children. Perhaps he remembered my grandfather, who was fluent in five languages but didn’t graduate from high school until he was 21 years old. Perhaps my father, as a man, an American man who grew up in the 1950s, couldn’t quite empathize, couldn’t quite anticipate the isolation of his wife, the strain on the relationship between her and her daughter. Perhaps part of him enjoyed being everything for her, doing everything for her. Or perhaps he tried and failed or tried and gave up, couldn’t surmount the challenge without such a massive imperative, without a spouse and a child and in-laws and friends and neighbors and co-workers and customers and cashiers who understand and speak only English.

Even now, as I try to learn, listening to a Pimsleur lesson every day (well, almost every day; sometimes every other day or every other week) for going on two years, I can barely utter more than a few words and phrases. It is too hard to retain, to pay attention, to think and speak in a language that isn’t mine, isn’t necessary. I am too dependent on English. I am too American.

***

In 1972, Okinawa reverted, or, rather, was “sold,” back to Japan for the sum of $685 million.

The Okinawans who were skeptical held their breath. The Okinawans who were hopeful celebrated. They sang and danced. They marched in parades and waved Japanese flags. They thought they were done with the U.S. military, done with the bases.

The bases remain.

Since 1972, nearly 9,000 crimes — including murders by shooting, stabbing, strangulation, vehicular homicide, theft, arson, rape, sexual assault — have been committed by U.S. military personnel stationed in Okinawa. One hundred sixty-nine court-martial cases for sexual assault — a higher record than at U.S. military bases in any other nation — have occurred in Okinawa.

Today, 20 percent of Okinawan land mass is still controlled by the U.S. military. More land controlled by a foreign military than in any other nation.

.

Okinawa became known as an “R&R island,” a place where troops could relax and recuperate between stints at war. My father was stationed on Okinawa after he fought for four years in Vietnam. He met my mother in Kadena, just outside the army base, at a club called the Blue Diamond, where she worked as a waitress, getting paid one dollar for every drink she got a serviceman to buy for her.

And here is where history becomes mine, alive in me.

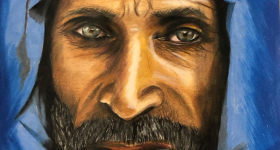

He sits on a stool. He is strong, confident. He is handsome, movie-star handsome, Elvis handsome. He smiles with straight white teeth and flashes a wad of crisp cash. He orders a bourbon on the rocks in a language and accent that signal power. She sits next to him. She is petite, slender. She is beautiful, exotic. She smiles and twirls a few strands of her dark, dark hair, as smooth as silk, flowing down to her waist like water.

Is love possible in a place like this, in a situation like this, between two people from separate worlds, on opposite sides of war and conquest?

I will never know how the story began, only how it ends.

Perhaps to someone who had grown up eating sweet potatoes for every meal, sleeping in the same room as her mother, father and six siblings, he must have seemed like a way out. Perhaps to someone who had just spent four years in combat, she was too vulnerable to resist. He had to save her.

And so, a year later, in 1974, two years after the reversion and one year before the Vietnam War ended, they married on the island. Marriage to locals was discouraged, but as a commanding officer my father granted his own approval.

It was a small ceremony. Only Obaa attended. My grandfather was too sick. My uncles were too angry. My aunts were too sad, scared, maybe jealous, that their sister was marrying an American, a soldier, that their sister was leaving. Obaa managed to scrounge enough money to rent two traditional wedding kimonos and hire a photographer to document the event.

My mother has seen her mother three times in the 45 years since she left.

***

While my mother and I lived in Okinawa, Obaa carried me on her back, walked the streets carrying me on her back, and pointed. “Ie” for house, “ki” for tree and “tori” for bird. She taught me how to say “taberu” if I was hungry and “nomu” if I was thirsty. She taught me how to say many words I can’t remember. My mother was grateful to spend this time with Obaa when neither of them had to work so hard. Back then, she believed she could have both: her life in Okinawa and her life in the United States. Back then, she believed she would return more often, enough to keep these separate worlds, Okinawa and the United States, her mother and her daughter, connected.

But even the best intentions dilute from routine and convenience. As I grew up, as I became more and more American, so did my mother. Visits became once a decade, and then once every two decades. Phone calls became once a month, and then once every three months.

.

While my mother and I lived in Okinawa, my father looked for a better job and a better place for us to live. A job and a place befitting his expectations and potential. He traveled to Brazil. He traveled to Singapore. He traveled to Tokyo and Osaka. He traveled to Texas and California and Washington, D.C. He was offered a job at the CIA but was told my mother would be a liability; he declined the offer. My father finally found a job as a management consultant for a financial firm called the Princeton Group. He found a place for us to live in Plainsboro, New Jersey, in a condo, in a complex of condos. Each building uniformly square, uniformly painted gray and blue, enclosed by parking lots and fences. The complex of condos shared a playground, two tennis courts and a pool.

In many ways, it resembled a military base.

There was a process, I’m sure, but in my memory, almost immediately I joined my father’s world. A world in which my mother was never entirely welcome, could never fully participate.

I remember she dressed up as a clown for Halloween once, but only once. I remember she helped us decorate the Christmas tree, but she wanted to wrap the lights too close around the trunk, not dangling closer to the edges of the branches.

I remember an older little girl from the neighborhood flung a shoe at my chest, knocking the wind out of me, and a sharp pebble at my face, slicing the bridge of my nose. I cried and ran to my mother, but she could see I wasn’t hurt too badly and did nothing. My father came home from work, and after I told him what had happened, he went on a hunt for this older little girl. He charged through the neighborhood, wearing his three-piece suit, searching every alley and alcove of the complex. When he spotted her on the playground, swinging on a tire swing by herself, he yelled at this older little girl until his skin reddened and his veins bulged, until she trembled with terror, until she cried and ran to her mother, and then her mother came pounding on our door, clamoring for an explanation. My father told her that he would have struck this older little girl if she were his own child and if she were a boy. He told her that bullies must be bullied; otherwise, they will never learn.

My father believed it was his duty to bully the bullies. He possessed an irresistible certainty, the assurance of someone who knew how it felt to do more than survive.

He always made me feel safe and protected in his world.

We lived in Plainsboro, New Jersey, for a year and a half. During that time, my father would travel to Manhattan on business trips for days, sometimes a week. I saw my father on weekends. I ached from missing him.

When my father was home, he would take me to the pool and we would swim laps. I clung to his shoulders, and his body held me above the water. My mother didn’t want to go to the pool. The water was saturated with chemicals, and the neighbors showered after — not before — they swam in the pool. The neighbors asked my mother to repeat herself, which annoyed her and seemed to frighten her. And her fear scared me, too. She didn’t belong. That meant I didn’t, either.

My father would watch Bugs Bunny cartoons with me. We sat on the couch together, eating carrots whole, as if they were plucked from the ground. My mother would peel and slice the carrots. She couldn’t understand why I preferred to eat the carrots whole, like an animal.

My father would sit in a chair beside my bed and read to me until I fell asleep. My mother couldn’t understand why I was so afraid of the dark, so afraid of this giant empty room that I was lucky enough to have all to myself.

Sometimes I would cry and cry from missing my father, and my mother would have to call him at work, because only his voice calmed me. His voice. The voice that read Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, The Ugly Duckling, and The Velveteen Rabbit to me whenever I asked and so often I had memorized the words. I remember one day, when I was 4 years old, I asked my mother to read these stories with me. I wanted her to listen and watch. I wanted to show off. We sat on the floor of my bedroom with the books spread between us. I recited the words and turned the pages.

“You don’t need me,” my mother said, bitter and accusing.

I didn’t bother to deny it. Even at that age, we both knew it was true.

.

I spent most of that year and a half with my mother, but my recollections of her are vague. She was a ghost who suddenly appeared in rooms, carrying a stack of carefully folded laundry or pushing a vacuum. She swept and mopped the floors, scrubbed the countertops, while I played with dolls that didn’t look anything like me and looked even less like her. She bought me a Mariko doll, the Asian-looking Barbie doll, but I was not amused.

She taught me how to fold paper into the shape of a bird.

.

Sometimes my mother got very drunk. She would call her mother and sisters in Okinawa, talk on the phone for hours, then hang up and burst into tears. For a long time, I thought my mother was weak. Because she couldn’t speak English very well or read. Because she was afraid of pools and neighbors. Because she got drunk and sobbed unconsolably, and had to be carried, sometimes dragged, to bed.

I didn’t realize then that she couldn’t change history, that history wasn’t her fault. That she could never escape the legacy of defeat, of trauma, perpetuated by her very own husband and daughter. That I could never escape, either.

Now, whenever I try to comprehend her loneliness, I am completely overwhelmed by her strength. She must have longed for that small child in the photographs. She must have ached from missing me.

.

My mother told me I used to understand and speak Japanese. She told me that, after we returned to the United States, she would speak to me in Japanese, and at first I responded, but then I stopped answering, and then, eventually, I stopped listening. Everywhere around me, English. Everywhere around my mother, English. I adapted. She could not. So I abandoned her.

My mother told me Obaa came to live with us for two months when I was 4 years old. She was supposed to come live with us permanently, but the United States, even just the sliver of it called Plainsboro, New Jersey, was too big and cruel for her.

I remember when Obaa took me to the pool. She wore a flimsy floral-printed button-down shirt and a skirt, and white sandals with white socks. She looked so odd and out of place in my world. She sat on a plastic lawn chair at the edge of the pool while I swam by myself in the shallow end and ignored her. Because she couldn’t speak English. Because she was old and wrinkled. From pushing a cart through the streets and rummaging through trash heaps. From watching a husband gamble and drink himself to death. From watching a daughter die of pneumonia, a daughter die of cancer, and another daughter move far away to another world.

I wish I could have made her feel more welcome back then. “Please stay with us, Obaa,” I would have said. “My mother needs you. I need you. Teach me Japanese.”

.

I imagine poor Shiro for those two months while Obaa was with us. Probably eating outside with the other dogs.

.

Shiro died shortly after Obaa returned to Okinawa, and Obaa never returned to the United States.

Comments