THAT YEAR is an independent clothing label and creative studio formed by Mao Kudo, Matt Jay and Janet Kang, three creatives and designers born in the late ’80s who draw on their nostalgic formative experiences as Asian diaspora coming of age in the ’90s and constructing identities through the discovery of Asian pop culture and subcultures.

Based in Portland, Oregon, THAT YEAR also has reach across New York, Japan and Korea. Hyphen spoke with them about how they make sense of their Asian diaspora childhoods, consuming Asian pop culture before the advent of the Internet, ’90s nostalgia and their new Summer 2021 karaoke-themed clothing collection.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Hyphen: When was THAT YEAR created and how did you decide to start putting it together?

Janet: We started talking about it in the summer of 2017. We’ve always been interested in the things that helped shape our identities and what we had in common was what we really loved about our childhood: J-pop, K-pop, dramas that we grew up with. The three of us started traveling to Asia together pretty frequently. We were all living in New York at the same time. And then we moved to Portland together to open our studio here [in Portland]. We started taking on more projects, both our own creative projects as well as design and cultural consulting work for clients.

Matt: We were all friends beforehand for a long time. Around 2017, everything started coalescing around specifically our experiences growing up being Asian American and specifically not really growing up in Asian communities. Mao is born and raised in New York City, Janet is originally from Los Angeles in California, I grew up bouncing around Portland [Oregon] and Tokyo. Aside from Tokyo, the three of us didn’t grow up with Asian communities. A lot of the way we accessed or started thinking about these early notions of identity and culture was through Asian popular culture. And because of our age, it just so happened that that’s Asian pop culture of the ’90s. Again, like Janet was saying, it was really important pop culture — J-pop and K-pop, dramas and television, Hong Kong cinema and all different kinds of sources from fashion to food to television.

The genesis of THAT YEAR was really a personal project — whether it be creating our clothing line or whether it be our pop-up events or whether it be an art exhibition that we organize. The core of it was really, for us, a way to explore and celebrate all of those identity-forming sources that we grew up with. We look back at those things, mine them.

Shirt from THAT YEAR's new Karaoke Club collection.

Hyphen: It sounds like even though you grew up in metropolises (like Los Angeles or New York), you still describe not being part of an “Asian community.” Was the consumption of Asian pop culture a solitary act or did you do it with Asian American friends?

Mao: I didn’t go to Japanese school. I learned the language solely from speaking it at home. My mother was a television reporter in Japan, and so speaking the language properly was something I learned from her. My father would rent recordings of Japanese television programs on VHS tape, and through those I learned a lot about Japanese social dynamics and cultural behavior. I was always curious about the gap between what I saw on those tapes and my own experiences.

When I was young, I visited my family in Japan every year and attended summer school there. It was always a stark contrast with my other life in New York, where I attended school with very few classmates of color, let alone Japanese, even though we were in New York City. So I kept the extent of how much I identified with Japan to myself mostly, but I am sure people around me could visibly see my influences through the clothing, accessories and media I had.

Janet: Looking back on it, I was kind of forced to go to Korean school [in Los Angeles]; it was a big part of my life. And at home I was watching Korean shows. But I don’t think I really appreciated it until I like moved away and got older. I wasn’t curious before. I think I needed to go through this phase of doing my own thing. You grow up trying to be American, but later on you actually realize it’s more important to hold on to what is your family heritage, and that’s more meaningful.

I grew up in Koreatown, but when I go to Korea I still feel like an alien. Where do I belong? There’s so much still to learn. So THAT YEAR has been really fun, just diving into all of that.

Matt: My early childhood was in Portland — the whitest city in America — but somehow I never grew up feeling “othered” there. So I was fairly unaware of my own identity for my younger years. I am also two-and-a-half, or three, generations Chinese American. So there wasn’t a lot of cultural tradition at home. My mom is from Queens, New York and my dad is from Columbus, Ohio. So my early childhood in Portland was just not being aware of my culture very much. That obviously all changed when we moved to Japan.

I was in Tokyo for junior high school and most of my high school years. That was the most pivotal time in my life. Spending your adolescence in a culture like that was really important. By the time I came back from Japan to America, I had a much more solid sense of my Asian identity. Your adolescence is the time that people struggle the most with identity, and being in Tokyo provided for me a completely different setting to spend those formative years. By the time I got back to America, I couldn’t care less about assimilating. I purely had a pride in and an interest in Asian culture without that struggle of wanting to fit into the surroundings around me.

Hyphen: Some of you mentioned how you felt like an alien — for example, Mao, you said you were bullied in Japan, or Janet, you mentioned not feeling like you fit in when you go to Korea. But it sounds like even though in Asian society you felt outcast or like you don’t fully belong, there was still this feeling of interest and wanting to consume culture from Asia. When you were watching these shows and listening to that music, how did you reconcile that with your experience of being in that society and being treated as an outsider?

Janet: I wasn’t bullied. It was more internally, I had a feeling like I am not really Korean. But I look Korean. So it was more about understanding my dual identity. So when I consume the pop culture, I just see it as Korean culture which is something I want to know more about. I don’t feel bitterness.

Mao: I did experience some bullying while attending Japanese school while visiting my grandparents for the summer. I had my ears pierced at a really young age, and I got picked on for that since no Japanese kids that time would have their ears pierced at that age. I was from America and spoke the language but acted differently. So I remember them calling me a UFO, which was actually really funny to me, since I also loved The X-Files.

My grandfather was really strict. When I would get into trouble outside and come home upset, he would always put the blame on me. But it never made me think of them any less since at the end, my grandfather and my grandmother always supported me and sent me beautiful handwritten letters that my mother would read out loud to me. I remember feeling melancholic seeing my name written beautifully by my grandpa, “真魚."

My all-time favorite Japanese drama from my early teens was Long Vacation, starring Kimura Takuya and Tomoko Yamaguchi. That was a really inspirational drama for me. To this day, I watch it every summer as a ritual. I wanted to be in Japan and wondered what it would be like to live there as a young adult, just like Long Vacation portrayed. The dramas and music were entertainment, but I also used them as a tool for research at a young age.

Hyphen: Could you describe some of the influences behind the original items from your store? For example, the Long Vacation hoodie, the MiniDisc T-shirt, etc.

Matt: So all the dramas that we did products for are, obviously, ones that were highly personal and significant in their own individual ways. The Asunaro Hakusho tee was one of the first pieces we made for THAT YEAR. Asunaro Hakusho is about a group of friends in college who meet in a book club on campus and follows their lives over the course of many years. It’s very sentimental. We liked the connection between the show’s plot and the forming of our own group as well. What we decided to do with that was we took a pretty rare candid cast photo of them, and we printed it on the inside of the chest pocket [of the T-shirt] to allude to that sense of sentimentality [of having your friends] with you. The back has the final screen text that pops up in the last shot of the drama. That was one of the first shirts we made.

As Mao mentioned, Long Vacation was a really important drama to us. It was something Mao grew up with, her dad would bring home these VHS tapes from Japan. When I moved to Tokyo in 1999, there were reruns on TV all the time and I remember it from that period. With those pieces, we worked with a friend of ours who runs another brand called Felix House, which is based in Tokyo and specializes in upcycled pieces and highly artistic embroidery. And he did the embroidery for those sweatshirts and that image that’s on the front of the sweatshirt. It’s a billboard that sits on top of the main character’s apartment. It reoccurs a lot, that image. So if you grew up with the drama, you’ve seen it; you definitely recognize that billboard.

A lot of the pieces that we make use these graphic references or iconography from these dramas that are — you can say — in a sense, very insider references. But if you grew up with the things that we did, they’re not so obscure. You recognize them right away. And to tie that into the bigger picture of what THAT YEAR does, part of our ethos and how we work is by creating things that are by us, for us. We don’t worry about who gets it and who doesn’t and who will appreciate it. We want to celebrate these references, and we bring people along for the ride if they want.

But if you grew up with the things that we did, they’re not so obscure. You recognize them right away.

Mao: The Asunaro Hakusho T-shirt was the beginning of THAT YEAR, because all three of us were re-watching the drama at the same time. And we realized that the first thing you want to do as a fan of something is to look for the merch. Even in those Japanese dramas, at the end of episodes, there would be a clip where the actors said thank you for watching, and if you mail in something to this address, the person who wins will get this signed CD or something. So we were saying let’s go on eBay, let’s go on Etsy and look for old merchandise, and then we realized, why don’t we just make something ourselves?

And this took us to this much deeper conversation of what does this all really mean to us. We made the T-shirt. And during that time we were also invited to do our first event in Portland. The friend who invited us asked us what we wanted to be called. We came up with THAT YEAR because it evokes this ambiguous, nostalgic feeling that also seems to point to a specific time. We felt that everyone would have their own “that year” as well. Everyone is able to connect to it, and say, “I have my own that year.”

Hyphen: It’s a really resonant name because so many diasporic Asians feel that kind of nostalgia and longing. Since you’ve started the label, what have been some of your most popular events and products?

Matt: They’ve all been so different, it’s hard to say which one was the most successful or which one was the most popular. The format of most of our pop-up events is a sort of re-interpretation of nightlife drinking culture. This is something we all miss when we’re here [in America]. So in our event space (downstairs), we created our own version of a Korean pojangmacha drinking tent alongside our own version of a Japanese yatai (food stall) that you might find outside a subway station. Pre-COVID, obviously, we had these big parties where people are invited to come in and have that experience. And each time we are showcasing some launch of a product or some theme around a drama or something.

Before the pandemic, these were pretty much seasonal and were a regular way for us to bring people in and share all of these references and things that we’re working with. This was an important thing for us to do in counterpart to the clothing and products that we make. The best way for us to share these things is through dialogue and the physical experience of being in an immersive space.

Hyphen: And it sounds like your clothing and events are reaching people who may not have the same set of cultural references. They may just be intrigued or like the aesthetic.

Matt: The events have definitely attracted a pretty diverse group of people. They are definitely not exclusively Asians, and they’re not people who necessarily have all of the same reference points that we have. But the people who come and who are in our community who have really supported us appreciate the fact that we are expressing something that is so personal to us and opening it up for everyone. And that is another layer of THAT YEAR: This is our story and our background and a way for us to encourage everyone, no matter what their background is, to embrace their own references and nostalgia.

Hyphen: Can you tell me a little more about the inspiration for your new collection?

Matt: The theme of this collection is karaoke. Karaoke is, of course, one of our favorite pastimes and a way we bond, specifically Asian karaoke. We were envisioning pieces that we thought would look incredible in that specific setting — in that darkened room, with that lighting, those colors, that vibe. The collection has a lot of fun reflective details and trims — pieces that would catch light in interesting ways if you’re taking photographs with your friends in karaoke rooms.

It’s the first full cut-and-sew collection that we’ve made. The whole collection was a great way for us to challenge ourselves and to make things from scratch, from the ground up, and make more intricately designed pieces. We collaborated with a lot of different amazing craftspeople and artists. One was notably DAAG, a creator who makes custom pieces for people. It’s not a brand that he sells in stores, it’s really a personal project for him. He’s also an artist. We worked with him to make a jacket and pants set for this collection.

Set from THAT YEAR's new Karaoke Club collection.

Mao: We also worked with local Portland creatives and kept in mind the Portland lifestyle. It’s a bike town, so we also thought about that with a placement of certain details on garments, like, if that person is biking home from karaoke.

Matt: One particular piece we are excited about is this workwear set. It appears to be a classic Carhartt-like workwear jacket and pants set, but when you look at it more closely, all of the pockets are designed specifically in proportion to karaoke items. So there is a pocket that fits the remote, a pocket that fits the microphone, a coin pouch for your Asian coin karaoke. And it has a particular button on the collar that references Japanese school uniforms. So we have this fun mixing of cultural references there.

Hyphen: I’m curious about your connection to ’90s culture. What is the difference between people of the generation who grew up with ’90s culture versus your parents’ generation and Gen Z now? How has identity formation and consumption of Asian culture changed as Asian culture has entered more of the mainstream recently?

Mao: I think all three of us noticed that. Especially our parents’ generation. You can see the difference in thought. My parents came from Japan hoping to live their dreams; my mom and dad were aware they might not become wealthy Americans, but they thought their personalities were more suited to America than Japan. Also, my parents were into American pop culture. My dad came to America with nothing and taught karate at a dojo on West 4th and worked at an army vintage store and later worked as a travel agent. My mom was a reporter in Japan, and she was actually more successful there than in America.

Seeing the younger generation now, it’s interesting to see how much more vocal they are [about Asian identity]. I feel kind of old.

Matt: I think one of the key generational things we experienced, which was very important in forming how we see the world as opposed to the generations immediately before or after us, is obviously information technology. We are the last generation to grow up — for a portion — without the Internet, and then coming to it. And not just the Internet, but all that comes with that as a way to see the world. We’re the only generation that still remains with a sense of place that is very important and helps shape who you are.

Now, we are in a much more globalized world. If you grew up in Portland now, it doesn’t mean you don’t have access to all the same cultural information as someone in New York does. So I think for kids now, the world feels much more borderless, and influences and references come from everywhere. The main influence is just what is collectively being shared online. In our generation, I think there was something that was much more specific about being a Japanese American in New York City in Washington Heights, a particular neighborhood. I think that is slowly being lost — not for good or bad — but it is something that has changed.

Janet: I feel like when we were younger, we cared so much about what kind of people we were, and we had to be authentic and real. Trends came so slowly. You only got to know what was out there when you saw something at school, went to the mall, saw magazines or catalogs. Trends use to move by the decades, but now they move all at once. Now when people reference the ’90s, I wonder how deeply they actually know about it.

We have a lot of Asian American friends our age and we always ask them, do you remember this or that. The ’90s is such a specific time period, and that’s why this project has been so fun for us.

Mao: I remember when I was young, on the first day of school after summer vacation, all the kids were expecting to see something different about a classmate. I started my school year inspired by the Japanese Ko-gal look and mixed that with what I loved to wear at the time, which was my army green UFO pants.

That was something we [at THAT YEAR] often reminisce about too: the little things we carried, like Japanese stationery or a planner. These signifiers of identity.

Janet: We think we are our only generation, but for example, my sister, who was born in ’91, went through some of the same references I went through. She is aware of some of the same things, but it probably didn’t hit the same.

Hyphen: All your memories are so tactile, too, like writing things down on a piece of paper or calling with a landline. Young people these days probably long for that tactile feel because the digital world is so not tactile.

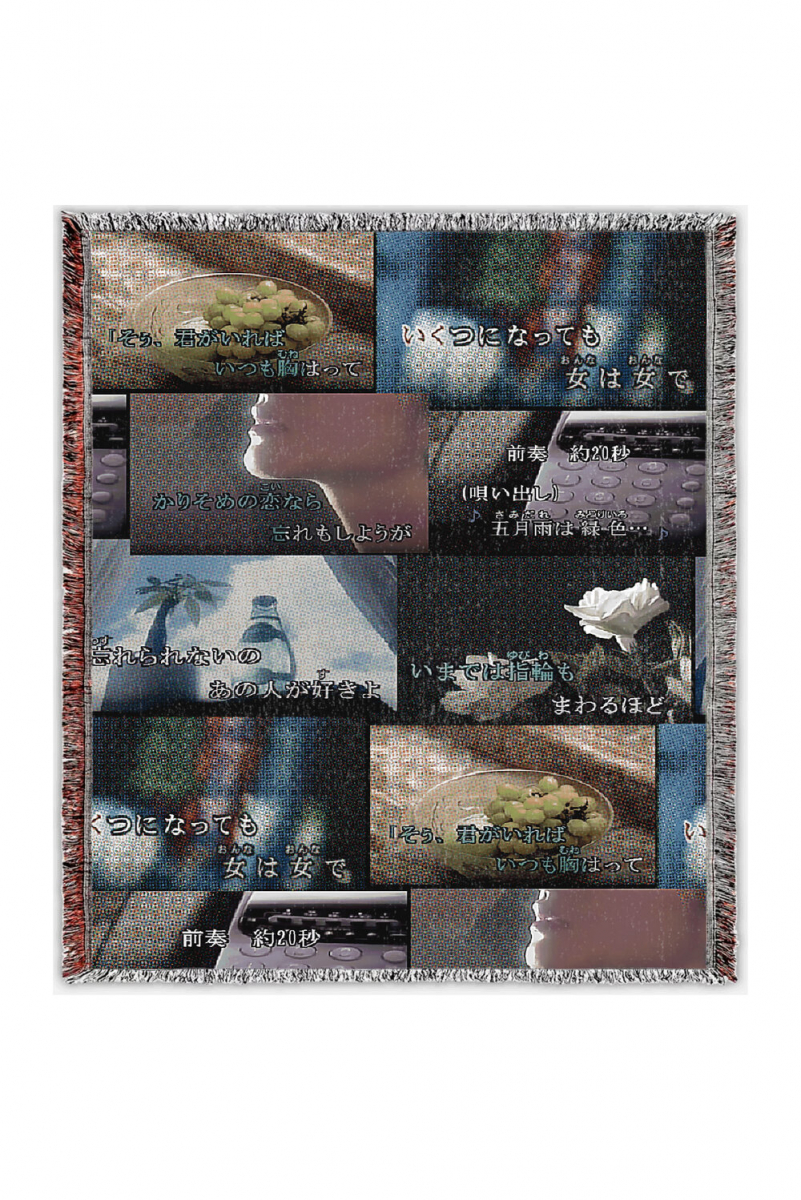

Woven blanket from the new THAT YEAR Karaoke Club collection.

Hyphen: Could each of you pick a memorable reference that you would like to introduce to our readers?

Matt: Long Vacation is definitely one of them. It’s not an obscure reference if you grew up in Japan in the ’90s; it’s as common as Friends in America. Everything about it is amazing.

Mao: One of the most exciting things that happened to us was getting to interview a singer named Anna McMurphy, who was the lead vocalist for the band Cagnet. Cagnet was from America, but they had a period of notoriety and success in Japan in the ’90s after they created the soundtrack to Long Vacation. We tracked Anna down and messaged her asking if we could record an interview with her as part of a Long Vacation themed event we were doing. It was so exciting.

Matt: They were an American band that got recognized by a Japanese producer, who then brought them onboard to do the soundtrack. They went on for a while after that continuing to create music for popular Japanese dramas. For us, it was such a big deal because of how much Long Vacation meant to us and how we can recite those songs word for word. We recorded that interview with her and turned it into a little video piece and played it at our event. No one who came to our event knew exactly what this was, but it was on display because it was so meaningful to us.

Mao: Another reference is Yazawa Ai’s mangas. She was an illustrator and writer whose stories were published in Ribbon. Her manga were such an inspiration for me. Neighborhood Story (Gokinjo Monogatari), NANA, Paradise Kiss were my favorites. Her illustration style, the characters, the fashion, everything about her work is so cool. But the most important aspect is how deeply human her storytelling was.

Janet: H.O.T. was definitely big for me when I was going through the Korean phase. In 7th grade, when they were really big, I decorated my locker with them. My favorite memories of Korean things growing up was watching Music Bank and listening to the top singers of that time. K-pop from ’96 and ’97 were very influential to me. Back in the day, if you wanted to hear your favorite song you had to call in and request it. It blows my mind to think that now, you can play whatever you want. Back then, if you had a famous song, it stayed up there for a long time, everyone knew it, was on the same page. Also, Morning Glory stationery.

Mao: I used to watch this Japanese music show, Hey! Hey! Hey! Music Champ. It was on at 8 am after the morning Fuji News. It was hosted by two Japanese comedians who sat down with special music guests each episode. There was also a section on the show where they would show mini clips of MVs and went down the top 10 music ranks. I would sit there with a notebook and I would write down all the titles and artist names. I would put a star next to it if I wanted to buy the single.

Sometimes friends of family or my dad coming back from business trips from Japan would take my list and bring back the singles I wanted for me. I would call my cousin Yui once every month — the call was so expensive — with limited time, and we would talk about what we were listening to, what was popular, and I read my list of songs asking her if she listens to those bands and songs as well. My favorite artists during that time were Amuro Namie, Spitz, Mr. Children, X-Japan, Speed, Dragon Ash, M-flo, Rip Slyme, Chara, Blue Hearts, Utada Hikaru, Mongol 800, My Little Lover, Glay, Elephant Kashimashi …

Janet: Did you watch Reply 1988?

Hyphen: Yes, I watched all three of the Reply series.

Janet: That is one of my top recent dramas.

Hyphen: Finally, do you have any creatives you want to shout out?

Mao: We would love to thank some of the artists and creatives we have collaborated with through THAT YEAR. SimJae, Primary and his Paktory crew in Seoul. Felix House, Chisei Kobayashi, Naoki Usuda and Hiroya Anjo in Tokyo. Hyun Jung Jung, DAAG and Jessica Waltz in Portland. Sekou Younge in New York!

Janet: I have my own brand too, ilgi, which means “journal” in Korean. I make textiles with prints and patterns from memories of me living in New York or visiting Korea. My most popular print is one for which I took pictures of grandmas on the street and matched them all together. On my website I have the backstory of every print and how it came to be.

THAT YEAR’S summer 2021 karaoke collection is available now on thatyearforever.com.

Janet Kang’s label is also available at ilgistudio.com.

Comments