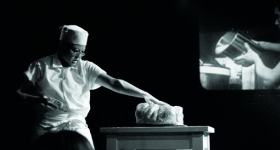

Photographer Hatnim Lee

THERE ARE CERTAIN things that may mark a person as successful.

It may be a gorgeous home, a successful career, a life shared with a husband named Oliver whom you met while getting your master’s in architecture at Yale, but that isn’t what defines designer Jean Pelle (although she can lay claim to all these things).

Her story is shaped by what she had and what she didn’t, and the things that bubbled up along the way.

Visiting Pelle’s studio today, you see what she does have: a distinct vision of simple and refined forms that translate to an unhurried and timeless beauty. The curves of her Tod candlesticks are unadorned, except for the wink of a thin stretch of 24-karat gold leaf tracing one ring of exposed wood grain. Clear glass orbs combine into a chandelier that successfully mimics champagne bubbles.

Her studio is luxe in a manner that allows character and class to trump ornamentation and braggadocio. You want to pick up and touch items — but don’t, for fear of getting fingerprints on them.

Here’s what Pelle would say to that: Pick it up. Get it dirty.

As a toddler, Pelle created beauty from the simplest stuff around — dirt — and found her calling. “[In Korea,] I would play in this gardening area my mom had, and I would mix up mud to make fake ddeok. … I’d make them the way the older women would make it, and stuff the cakes — everything made out of mud.”

When Pelle was 5, her family moved from Korea to Los Angeles, where she became familiar with the struggle between wanting to make art and needing to make a living. Kwang Hwee Kim, Pelle’s father and biggest influence, ran his own studio there for more than 20 years, creating sculptural prototypes for manufacturing forms. Pelle helped as an assistant in his studio.

Then the economy shifted. Specialized labor began moving

overseas to China, where everything was cheaper. Economic hardships affected Pelle’s family — and, ultimately, created the circumstances that spurred Pelle to design her first house at age 12.

“When I was a kid growing up in L.A., I remember thinking that it had to be the ugliest place in the world. There were really no buildings to admire.”

Her family’s home contrasted dramatically with living spaces she saw in her neighborhood or on TV. Their traditional Craftsman bungalow, with arched ceilings and intricate detailing, was transformed into a vibrant home business. “My mother had a daycare center at our house. … There was no living and dining room to speak of. Our fireplace was covered up with a bulletin board, with all these stenciled cutouts for the kids.”

As an architect and an artist, Pelle believes in the whole picture. Even with her young eyes, she respected the vision of her home’s architect. There were things that were always meant to be there — such as the chandelier.

“There was a day they took down the chandelier from our living room. Our living room had high ceilings and the chandelier came with it. I remember my mom helping my dad take it down to put up an ugly, long fluorescent light for the business. Can you imagine fluorescent lighting in your living room?”

Pelle laughs, then pauses: “It really mattered to me. It was so important to me at the time.”

The loss of the chandelier compelled Pelle to take matters into her own hands and begin creating her own visual representation of a home. It was a prescient nod to her future master’s degree in architecture.

“I had this fantasy sketchbook that contained the nicest furniture I saw then, from Ethan Allen and Sears catalogs,” she says. “I’d cut out the photos and place them in correct perspective.” She called the sketchbook “My House.”

Years down the line, a career as an architectural designer in California and New York made way for an opportunity to work with her hands. During two heady weeks in 2008, she quit her job, found a studio and applied for a business license. Jean Pelle, the company, was born.

Today, Pelle runs a growing business that fills in the blanks left by a missing childhood chandelier, creating graceful objects for the home.

“I didn’t realize how much I really wanted to do it until I was working years and years behind a computer, at a desk, and felt it wasn’t really me. I really wanted to go back to my roots. That’s what really defines me, this making stuff.”

Han Pham is Hyphen’s Takeout editor.

Comments