Growing up in 1980s Southern California, Minh-Ha Pham remembers accompanying her mother as she shopped. But instead of returning with arms full of shopping bags, her mother brought back a head filled with inspiration. “We were poor so we didn’t buy anything, but she’d spend hours studying clothes,” Pham says. “Then she’d go home and make it.”

A skilled dressmaker, Pham’s mother created much of what her children wore, and, for her own uniform at her bank job, she crafted chic secretary blouses with the large ascot bows that were so indelibly of the ’80s moment. “The big shoulders, the whole thing,” Pham says with relish. “She ended up giving most of that stuff to Goodwill. I would love it now.”

That type of appreciation tinged with grief for fashions lost is why she has started Of Another Fashion, an online repository of the often-ignored fashion histories of everyday American women of color through old photographs, some reader submitted, some archival.

Pham, an assistant professor in the art history and Asian American studies programs at Cornell University, says the project began in 2010 with a question: What other fashion histories do we not know about? She recalls visiting museum exhibitions about American fashion, focused on couture or designer fashion, and sensing something missing from those presentations. “Women of color historically didn’t have access to those luxury fashions,” Pham says.

Her project, which she hopes to develop into a museum exhibition, aims to reveal these histories as well as to reimagine the American fashionable body (which Pham calls “an implicitly white, thin body”) and by extension, rethink women’s roles in American history and popular culture.

Her goal is also to send women digging into their closets, attics and basements to provide her with artifacts for which no archive currently exists. Pham’s collection thus far is small, and one problem is that many pieces of clothing have been lost over time — a casualty of these fashion histories not being considered significant, according to the scholar. “For a lot of women of color, they didn’t buy Chanel or Gucci,” Pham says. “They bought secondhand or homemade their clothes or altered budget-label clothes bought at Woolworths. Fashion is about the original design. Well, that doesn’t really exist here, among these women.”

Class is as much an issue as race in whether a garment was prized and conserved, and many working-class women of color just didn’t see their clothes as worth saving. “A lot of women of color have internalized the idea that their clothes and their fashion history don’t matter,” Pham says. “‘Am I really gonna pay to have it preserved if I bought it at Woolworths or JCPenney? The museums tell me it’s worth nothing. There aren’t fashion histories written about it.’ No, you don't keep it. You don't honor or respect it.”

But, ultimately, she wants fashion to be fun. “When you talk about women of color and fashion, we usually talk about sweatshops or racism in fashion magazines. But we don’t talk women of color having fun with fashion. Fashion is a cultural force — it’d be silly to think that it somehow missed women of color.”

Alice Ishizaki, photographed in Los Angeles in the 1930s, was the first Asian American to be hired at either The Broadway or Bullock’s department stores in Los Angeles, according to her family. Although the department stores had policies about not hiring women of color, her granddaughter Cheryl Motoyama says, “They hired my grandmother on the spot when they saw her because she had flawless skin. She worked for a number of years at their makeup counter.” Ishizaki, ever-fashionable at 98 years old, continues to use Elizabeth Arden day and night cream, and her beauty advice includes wearing sunscreen, bright lipstick and gloves. Courtesy Cheryl Motoyama.

Women preparing backstage for a benefit fashion show at the legendary Ciro’s nightclub on Sunset Boulevard in 1950s Los Angeles. Mary Kitano (holding mirror) and Lily Shitara (center) were popular professional Asian American models. Courtesy Toyo Miyatake, Rafu Shimpo Collection, Japanese American National Museum.

Mexican American flappers Eloise Arciniega and Hortensia Arciniega (wearing a hat) in Long Beach, CA, in 1928. Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library.

Fashion designer Kow Kaneko (seated) with two clients in Pasadena, CA, in 1958. Kaneko, whose work was featured in Time and Look magazines, created gowns for beauty pageant contestants, movie actresses and society matrons. Courtesy Rafu Shimpo Collection, Japanese American National Museum.

Norma Campagna as a nursing student in the Philippines in the 1960s. Courtesy Theresa Campagna.

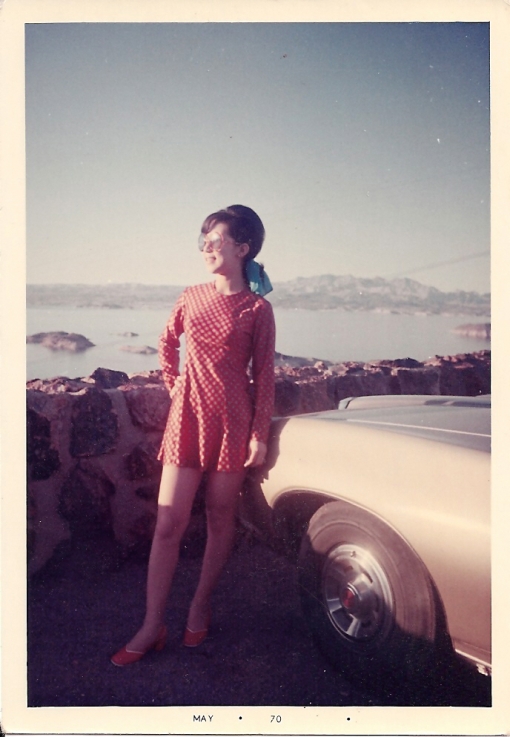

Wei-Kuo Liang visiting Hoover Dam in 1970 at age 26. She was a stewardess for China Airlines, and according to her daughter Gracie, “this allowed her the freedom to see the world, and undoubtedly expanded her life and fashion horizons.” She added that her grandmother had “stressed the importance of not bending over in this dress.” Courtesy Gracie O.

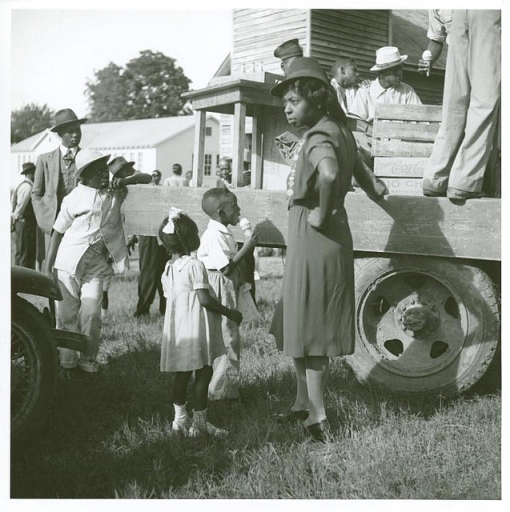

A woman buys ice cream for children from a truck in Natchitoches, LA (ca. 1940). “My guess is that this photo was taken after church,” Pham says. “Everyone seems to be in their Sunday best.” Courtesy Farm Security Administration Collection, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

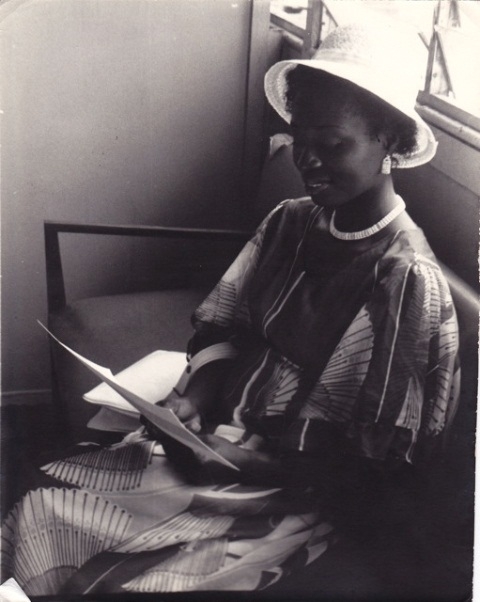

Alice Antwi on the day she obtained her marriage certificate in Ghana in 1980. Courtesy Ama Kyere.

Grace Lee poses for a photo in Long Beach, CA, in 1932. Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library.

Marylou Martinez and Mary Puga (standing left to right) prepare to go out with friends (ca. 1964). Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library.

Ogretta Greene Robinson (right) and her cousin Denise Hodges in the mid-1950s in Muskegon, MI. Hodges later tried her hand at modeling in Chicago. Courtesy Victoria Greene.

Comments