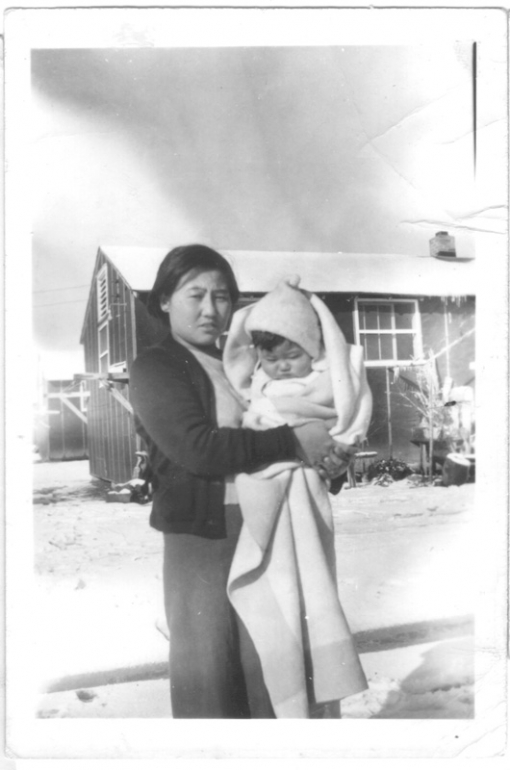

Since I was very

young, I have seen photographs of Jerome, AR. In one, my grandmother is

standing in front of a black tar paper-covered barrack. She is holding my

infant mother, who is wrapped in a wool blanket, a white cap on her head. There

are icicles hanging off the rooftops. The landscape in these photographs is

stark: miles of farmland and swamps, massive dark foliage and the visible chill

of the Arkansas winters.

The writer's grandmother and mother at Jerome, 1943. Courtesy of the writer.

The writer's grandmother and mother at Jerome, 1943. Courtesy of the writer.

When I first heard about Drama

in the Delta, a new video game that takes place at the Arkansas Delta

internment camps for Japanese Americans, I wondered how — or if — it was

possible to construct a video game from an experience that I understand, as the

daughter and granddaughter of Jerome internees, as a time of irretrievable and

traumatic loss.

But Drama in the Delta —

a collaboration between the Supercomputer Center and the theater department at

the University of California, San Diego — turns out to be a surprisingly moving

experiment in historical simulation. This past summer, a free download of the

game’s initial level became available on dramainthedelta.org, allowing players

a 3-D glimpse into the lesser-known Jerome and Rohwer, AR, camps, the only

detention centers located in the racially segregated South.

The game’s first mission — additional levels will be released

as the project receives further funding and public feedback — establishes

the setting and mood of the Southern camps. The game

takes place in 1944 on a day that the majority of internees are leaving

Jerome. Players run through the empty camp as Nisei teenager

Jane on a mission to retrieve beloved objects accidentally left behind.

There is a sense of the desolation and repetitive nature of the

space, the blocks upon blocks of barracks.

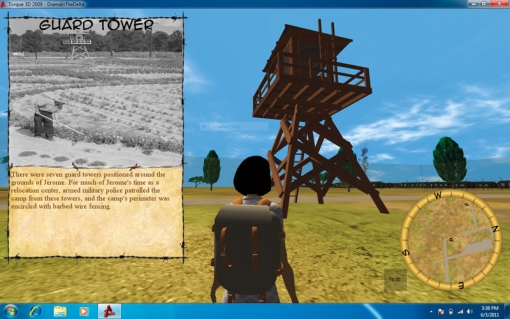

Jane approaching a guard tower at Jerome, in her search of her friend Akiko's belongings.

Jane approaching a guard tower at Jerome, in her search of her friend Akiko's belongings.

Delta is part of a genre of social justice-oriented gaming, which

capitalizes on the ability of a video game to be both an aesthetic

and educational experience. Websites like Games for Change

(gamesforchange.org) showcase digital games that draw upon the

expertise of academics and designers alike and intend to educate

audiences about history and social issues by immersing players in

visually stunning, elaborately fashioned worlds.

Jeff Ramos, a content manager for Games for Change, says that

such social justice-oriented gaming allows for deeper levels of interactivity.

“The ability to enter a different world and affect it, and be

affected by it, creates a unique form of impact and understanding

not commonly found in traditional media,” he says.

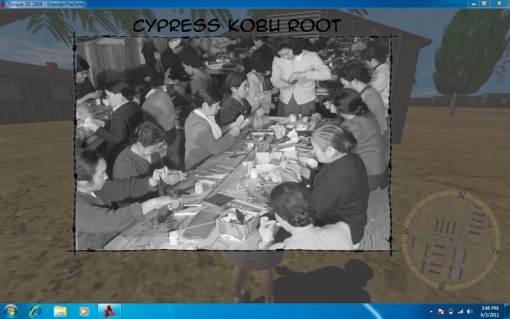

Photograph of internees creating sculptures from kobu, the root growths of cypress trees.

Photograph of internees creating sculptures from kobu, the root growths of cypress trees.

Emily Roxworthy, a theater professor at UCSD, leads the Delta

project, and her research on the internment camps serves as the

historical and theoretical foundation for the game. While a graduate

student at Cornell University, Roxworthy started her investigation

on the role of performance — such as in Kabuki and Noh theater

— by prisoners in the internment camps. Such performances, Roxworthy

says, were a means of resistance against the scrutiny of

camp administrators and the public at large.

The video game centers on these performances and is populated

by scenes and characters as wide ranging as African American

day laborers who also sing in a blues group, Nisei teenagers

performing Kabuki and a “Womanless Wedding,” a long-standing

Southern tradition where men dress in drag and act out a wedding

ceremony.

Jane with John, a day laborer at Jerome.

Jane with John, a day laborer at Jerome.

The game also explores how the Jerome and Rohwer camps

were located at a complex nexus of race relationships in the American

South. In one mission that has yet to be released, Kenji, a soldier

in the 442nd all-Japanese American army regiment, arrives in

Hattiesburg, MS, and is directed to take a bus to nearby Jerome

for R&R. Caught in the middle of a black-and-white racial order, the

game requires Kenji to choose whether to sit at the front of the bus

with the whites or at the back of the bus with blacks.

“[Japanese Americans] were usually allowed, if they were willing

to accept it, the privilege of being white,” Roxworthy says, adding

that this scenario was based on historical accounts. However, most

Japanese Americans struggled against that “privilege”; they could

see what was happening to African Americans was unjust. “To pit

themselves against African Americans seemed wrong,” she says.

Roxworthy argues that the exposure of Japanese Americans

(who came from Los Angeles, Sacramento and California’s Central

Valley) to the blatant racism of the Jim Crow South may have

spurred later activism by internees. Civil rights pioneer Yuri Kochiyama,

Roxworthy says, was interned at Jerome, and she witnessed

firsthand the stark segregation between blacks and whites while

performing a play she composed to white audiences outside of the

camps.

In addition to replicating the era’s race relations, the team at

UCSD’s Supercomputer Center strived for authenticity in constructing

the visual world of the camps. They drew upon blueprints and

archival photographs to meticulously re-create the 3-D world of

Jerome. But the tendency of 3-D graphics to look plastic and sterile

made it difficult to create a faithful representation. One former

Jerome internee who consulted with the UCSD team on the game

found that the camp looked too clean and perfect. “We spend a lot

of time trying to degrade the environment,” Roxworthy says.

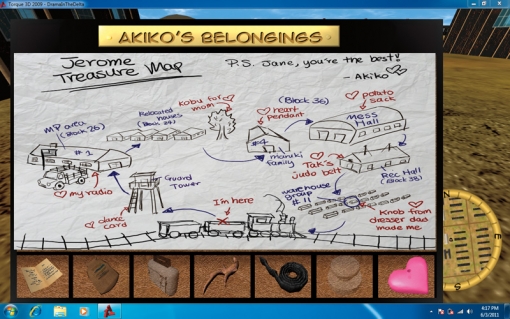

A map of Jerome camp, with the locations of Akiko's various belongings.

Despite efforts to make the game historically accurate, including

integrating informational passages and photographs into the

missions, there remain potential pitfalls in creating a video game

around a weighty historical topic such as the internment. “The

idea that the game would be all that someone might learn about

the camps is really troubling,” Roxworthy says, pointing out that

the Delta website provides more historical information and links

to resources.

A storyboard, used in the planning stages of game, of Jane holding on to one end of a paper streamer as a train is about to depart Jerome.

Ultimately, Roxworthy hopes Delta will provoke an emotional

reaction among players, namely empathy with the character being

played. When I finish the first mission, an animation plays of a train

about to depart Jerome. Passengers uncoil rolls of paper streamers

to those who stand below, those who will remain in the camp. As

the train leaves the station, the streamers become taut and break.

Illustration of Jane grasping at streamer.

Illustration of Jane grasping at streamer.

I am participating in a moment, in a place that I have only known

through black-and-white photographs. I am seeing Jerome in color

for the first time. And it is a remarkable sight.

Cathlin Goulding is a books editor for Hyphen. She last wrote about Mr.

Hyphen 2010, Kyle Chu.

Comments