Of all things, it was an episode of the ’90s sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air that tipped Catherine off. In it, the British butler, Geoffrey, made a joke about not having a green card. Innocently, the then-9-year-old asked her mother whether she had one.

“My mom was so distraught and flustered and said, ‘Don’t ask that,’ ” said Catherine, now a sweet-faced 23-year-old, who preferred that her last name not be published. “I didn’t even know what a green card was. I equated being an immigrant with being suspicious.”

Slowly, Catherine began to understand what it meant to be undocumented. One evening in high school, while eating doughnuts with her friends in a parked car, a police car rolled by. Heart pounding, Catherine’s thoughts ran to the extreme: The officers would discover she was undocumented, her mother (a legal immigrant) would lose her job and Catherine, her brother and father would be deported to the Philippines. She nearly broke down, but the officers let them go home after checking her friends’ licenses and Catherine’s student ID.

When she turned 16, she couldn’t get a driver’s license like all her friends. She declined admission to the University of California, San Diego, because her family could not afford the tuition, and she was ineligible for financial aid. She enrolled at a community college near the San Francisco Bay Area suburb where she grew up.

Undocumented college students like Catherine, who were brought here as children, are doing everything right on the path toward the American Dream. Even as some of the most privileged among the undocumented, their lives are tightly constrained: They cannot get a driver’s license, travel outside the country, vote or obtain student loans. And even after making it to graduation, they cannot legally work in the US.

“They’re doing everything that our society has asked them to do; they’re working hard, studying hard and they’ve been treated horrendously by our society,” said Kent Wong, a UCLA professor who teaches a course on undocumented students.

But perhaps the biggest barrier that Catherine and other undocumented Asian youth face is the pervasive silence: from a lack of visibility within the larger immigration movement to too few outlets to share their fears and frustrations with others, as well as stigma within their own families and communities. Combined with immense financial and academic pressures and little prospect of finding a good job without a legal status, many students face an overwhelming, voiceless struggle that often results in depression and anxiety.

However, Catherine is part of a group of undocumented Asian and Pacific Islander students who in recent years have become more outspoken about their plight. The API voice has been slowly growing in the debate around the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, a proposed federal law that would give college students a chance to become legal residents, under stringent guidelines.

Although the DREAM Act has seen fits and starts for over a decade, these students believe the time has come to step into the spotlight and advocate for themselves with urgency, due partly to the momentum in the past two years around the DREAM Act and to a widely read 2011 New York Times story in which Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Jose Antonio Vargas revealed himself as an undocumented Filipino immigrant. As Wong said, “The greater risk is to not speak out, to remain silent, to remain in the shadows.”

A Space of Their Own

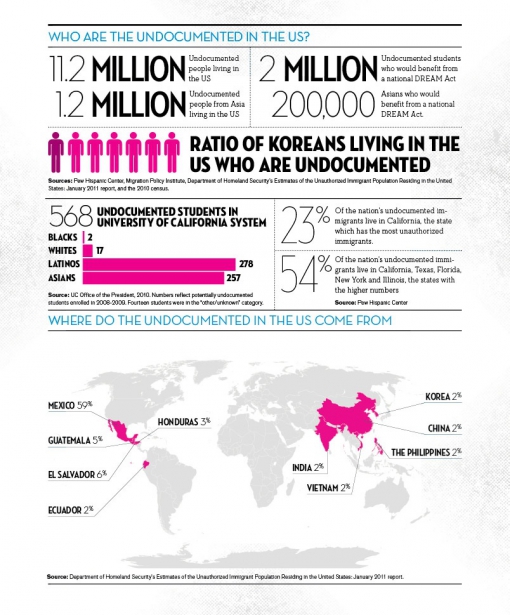

National coalitions for the undocumented population like United We Dream and dreamactivist.org are predominantly Latino, in part because the vast majority of these immigrants are from Latin America. Of the country’s estimated 11.2 million undocumented immigrants, only 11 percent, or 1.2 million, are from Asia; an estimated 2 million are undocumented minors or young adults under 30 like Catherine, and about 10 percent of those are Asian.

In the University of California system, approximately 500 – 600 undocumented students are enrolled, according to the University of California’s Office of the President, and an estimated 45 percent are of Asian descent, almost equal to the number of Latinos at 49 percent. But few Asians join undocumented student groups on those campuses.

Kevin Escudero, a graduate student at UC Berkeley who is writing his dissertation on Asian and Latino undocumented students, said that Asians may find it difficult to participate in groups that are heavily Latino. References are made in Spanish or to Latino culture. In one writing workshop for undocumented students, Escudero heard a poem read in Spanish; everyone laughed, but no further explanation was offered for anyone who didn’t understand. “In certain ways, those spaces are super Latino,” Escudero said about the undocumented student gatherings at UC Berkeley.

While undocumented Latino and Asian students face similar challenges, subtle differences in their experiences exist, experts say. Latinos face the stereotype of dropping out, while Asians are expected to succeed. Being undocumented is a more taboo subject among Asian students compared with Latinos, which can cause shame and anxiety. Yet Asian American students have fewer outlets to discuss their situation.

Catherine is part of a group called Asian Students Promoting Immigrant Rights through Education (ASPIRE), formed out of the San Francisco-based Asian Law Caucus in 2008 to support Asian undocumented students. According to the group’s former community advocate Lisa Chen, it is the only undocumented student group in the US that is pan-Asian, with people from the Philippines, Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, Mongolia, China and Hong Kong, as well as ethnic Chinese from South American countries.

While ASPIRE is a relatively new group, organizing undocumented Asian and Pacific Islander youth dates back to at least 2002, when a group of 30 undocumented API students from Los Angeles, Chicago and New York traveled to Washington, DC, to speak to legislators about their situations, according to Jane Yoo of the progressive advocacy group National Korean American Service and Education Consortium (one in seven Koreans in the US are estimated to be undocumented). It was perhaps the first national effort to give undocumented Asian youth a voice.

Compared with Latinos, fewer Asians have organized around this issue, and some immigrant advocates note with frustration that the majority of Asian Americans seem unaware of the undocumented people within their own communities. “I know many Asian Americans that work very hard and seriously on Asian immigration rights,” said Bill Ong Hing, a law professor at the University of San Francisco. “I just don’t think that the typical Asian American understands [the issues]. I think they are very much concerned with their own middle-class values and concerns. Unless something hits close to home, I don’t think most Asian Americans know there’s a serious immigration problem.”

An Asian Spokesman for Undocumented Students

While some students seek Asian-specific support, others have enthusiastically joined the broader, majority-Latino movement as well. Ju Hong, 22, is a senior at UC Berkeley and the university’s first undocumented student senator. Brought to the US from Korea at age 11 by his mother soon after his parents separated, Hong learned he was undocumented in high school when he didn’t have a Social Security number to put on his college applications.

As one of the few prominent Asian faces of the cause, he admits he’s come a long way, confidence-wise. “I was very embarrassed and ashamed of who I was,” he said, referring to his teenage years spent in Alameda, CA. “I thought I was the only undocumented student.”

Now at Berkeley, Hong is active in the campus’ predominantly Latino undocumented student groups, and he has learned to adapt. “Ju’s very in touch with Latino culture, like dancing and even speaking some Spanish,” Escudero, a friend of Hong, said. “He’s become very comfortable with hanging out with that community.”

Other Asian youth are also advocating for this cause alongside Latinos. In Los Angeles, more than a dozen undocumented students affiliated with the Korean Resource Center marched in solidarity with the 2010 Trail of DREAMs, when four undocumented Latino students walked from Miami to Washington, DC, to promote the issue. RISE (Rising Immigrant Scholars through Education), the heavily Latino undocumented student group at UC Berkeley, also just elected its first Asian co-chair.

To bring more attention to the cause, Hong has gone beyond student meetings to more direct actions. As part of a “coming out” immigration rally last summer to shed light on undocumented communities, Hong was arrested after he and six others blocked freeway traffic in San Bernardino, CA. “This is the right thing to do, because it will help my community and my family,” Hong said of his high-profile activism. “I shouldn’t be ashamed.”

Ju Hong, 22, an undocumented senior at UC Berkeley, is one of the more vocal API voices supporting the DREAM Act. He joins in a demonstration in Southern California and is arrested. Photo courtesy William Perez.

Like Hong, many undocumented students feel alone and isolated, forced to keep a shameful secret.

“As you’re growing up in high school and everyone’s talking about getting a driver’s license, and you’re not able to participate in those conversations, it begins to take a toll, especially at that age,” said Morna Ha, executive director of the National Korean American Service and Education Consortium (NAKASEC). “You begin to shy away from some types of conversations.”

Lisa Kim, 22, was brought to the US from Korea at 11 months old. It was meant to be temporary, but her father felt called to become a pastor for the burgeoning Korean American population, and their visas expired. Since then, all of them have been without legal status.

Kim admits to feeling depressed for her first two years of college. “It’s trying to juggle three jobs and trying to do college level courses, and I had to commute because I couldn’t pay for dorms. I couldn’t meet any friends.”

The myth that all Asians are successful only exacerbates the problem. “You have to live up to this standard of being perfect,” Catherine said. “As a result, there are voices being silenced.”

“The model minority stereotype can hurt API students, emotionally, mentally and support-wise,” said Katharine Gin, founder of the San Francisco-based nonprofit Educators for Fair Consideration, which gives scholarships to undocumented students and serves as a support network. “If you’re Asian, [teachers] don’t realize you’re undocumented. This can be an advantage, but it can also be hard not having anyone to talk to or anyone who understands your situation. And you don’t necessarily feel welcome in a Latino student group, where they are generally more comfortable talking about these issues.”

The silence extends to their families as well. Catherine felt like she could never talk to her parents about their status; each time she mentioned it, the conversation would be clipped short. Fabrizio Mejia, director of Student Life Advising Services and the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) at UC Berkeley, has worked with many undocumented students, and he said some stressed students consciously hide how they are doing financially and academically from their parents for fear of worrying them. “Their parents are so proud [because they are attending UC Berkeley],” Mejia said. “What the families don’t know about is the full struggle. [The students] want to have the image that they are okay.”

Anxiety, trouble sleeping and the inability to be vulnerable and establish trusting long-term relationships with people are common afflictions of undocumented students, according to Gin and others. “There are Asian students who think they are the only one who is undocumented,” Gin said. “That leads to quite a lot of anxiety, stress, feelings of being unwanted, of being less than human, that all of your relationships have the potential to be shattered if people find out something about you. You’re living in a house of cards. When people have to hide or have a big secret, everything feels unstable.”

And the constant instability can have dangerous consequences: Gin has found some students to turn to self-harm or become suicidal. Last year, 18-year-old Joaquin Luna Jr. of Texas committed suicide, and family members believe that his hopes of being an engineer were dashed because he was undocumented. Prior to his suicide, he had received letters from universities asking for proof of citizenship, according to news reports.

Part of the anxiety is the fear of being found out by immigration officials. Since 2011, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the arm of the government that enforces deportations, has publicly stated that they will not pursue deportation of DREAM Act-eligible students, in part because of a mandate from President Obama. Yet cases of deportation proceedings of undocumented students still regularly arise.

But students who have “come out” — whether through direct public action, online campaigns or interviews with the media — seem to have mostly benefited from the exposure, with many temporarily saved from deportation. According to United We Dream, a national coalition group advocating for the DREAM Act, none of the more than a dozen students who have come out through their network have been deported, and all have had their deportation halted due to their public campaigns.

One such student who benefited from publicity is Steve Li, a Chinese Peruvian student at City College of San Francisco. His case came to light in late 2010, when he was taken into custody and shipped to an Arizona detention center to await deportation to Peru. He received local and national media attention after his supporters wrote letters, called politicians and held rallies. During the month he was detained, Congress was considering the DREAM Act; he would have been one to benefit from the legislation. Li was given a stay of one year after Sen. Dianne Feinstein intervened.

While some undocumented students are on their way to earning a degree, many find it too difficult to afford without financial aid. Kim attended Loyola University in Chicago for three years but recently put her dream of becoming a doctor on hold, dropping out last fall to work in order to pay off the $17,000 that she owes the university. “It’s been a constant struggle with finances and paying down tuition,” Kim said.

It’s a common reality for many undocumented students. Since they don’t qualify for Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) loans, they can barely afford to pay the minimum tuition fees. Many of their parents are also undocumented and low income, working at places like dry cleaners or restaurants, if they are able to find work at all. Kim got a private bank loan during her first year of college, but the second year, she held three part-time jobs as a nanny, tutor and waitress — all under the table — while attending school.

Even at public universities, tuition hikes have left students struggling and taking a piecemeal approach to enrollment. “There’s a pattern of being in school for a semester and taking a semester off,” Mejia, the counselor at Berkeley, said. When they can no longer afford payments, they drop out to work.

In the past five years, tuition at University of California schools has skyrocketed, more than tripling from approximately $2,300 a semester for California residents in 2001 to $7,500 in 2011. In order to be officially registered, UC students must pay 20 percent of tuition, or $1,500 a semester. For some, that is simply too much to scrounge up. Catherine, for example, dropped out a semester because she couldn’t afford tuition. She was able to return after receiving three private scholarships for undocumented students.

Many undocumented students also commute from home or live in co-ops, and others are homeless or couch-surf, according to Mejia. He’s seen students doing all sorts of odd jobs: guinea pigs in studies, donating blood, waitressing and working at a chicken farm on the weekends.

In this respect, undocumented students might not sound much different from other low-income students, yet the former don’t qualify for federal loans and work study, and even if they excel academically, they have been barred from university scholarships. The result is that undocumented students take longer to graduate, if they are ever able to.

The biggest conundrum after graduating is finding a job without papers, and an odd byproduct of this problem is a desire by some undocumented students to stay in school forever. Mario is a 23-year-old Chinese Peruvian graduate student in engineering at California State University, East Bay, who will graduate in 2013. But, he said, “If the DREAM Act has not passed then, I plan to get another master’s.”

“A lot of us don’t want to leave school, because if we leave school, there isn’t anything we can do with our degrees,” said Mario, who did not want to his last name published. “I know a lot of people who have delayed their graduation because they are scared of that day coming. I feel like a lot of DREAM Act students are just stuck being educated, and we’re just waiting for the day we can give back to the community.”

A New Hope and a New DREAM

The DREAM Act is far from a panacea: Only roughly one in three undocumented youth would become a permanent resident if it passed, according to projections. They would first have to graduate from high school, then receive two years of college education or serve in the military for two years. But it’s the best chance for the nearly 2 million undocumented children and students in the US who remain in the shadows.

Groups like the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), a conservative nonprofit, have dedicated millions in the last decade to lobbying against immigration, with the DREAM Act their biggest target.

“As far as we’re concerned, it’s not about people’s ethnicity,” FAIR spokesman Ira Mehlman said. “It doesn’t matter if they’re Hispanic or Asian or white or black. America shouldn’t have to provide a solution to the problem that these people created.”

The bill again failed to pass in December 2010 by a narrow margin. Activists hope it will pass in coming years, but the bill will likely not be touched unless the Democrats sweep the White House and Congress in 2012. Then, the law could be reintroduced in Congress in 2013 at the earliest.

At the state level, undocumented students in California and about a dozen other states have it slightly better. Since California’s Assembly Bill 540 in 2002, undocumented students can pay in-state tuition — at a UC, that’s the difference between $15,000 and $38,000 a year. Undocumented students in most other states must pay out-of-state tuition. Since the federal DREAM Act is in hiatus, activists have been working on passing statewide legislation. In the past year, at least eight more states introduced bills that would allow undocumented students to pay in-state tuition. Conservatives have also been waging their legislative war, by passing statewide anti-immigration laws.

Last fall, the biggest glimmer of hope came with the passage of the California DREAM Act, which allows undocumented students to receive state loans and qualify for a host of scholarships that they were previously barred from — up to an estimated $14.5 million. California is the first state to pass such a law, and an estimated 2,500 students would benefit from it, according to the California Department of Finance, including the 140 undocumented students at Berkeley who had their tuition covered by private scholarships for the first time this spring. However, undocumented students still do not qualify for federal loans or work study.

She's still not comfortable talking with her parents about her advocacy work, fearing their disapproval. "I would have hoped that my mom would feel proud," Catherine said of what she hopes her mother's reaction would be, if she were to learn of all of her political activism. Catherine is unsure how she will be able to use her education to find legal, meaningful work. For now, one thing is clear: she'll continue to advocate for the cause closest to her.

Momo Chang is a writer living in Oakland, CA. This story was funded by a grant for immigration stories from the Rosenberg Foundation and the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

Why “undocumented” versus “illegal?” Being undocumented in the US is a civil, not criminal, violation, but the term “illegal” can be conflated with “criminal.” Immigrant rights advocates also say it dehumanizes people.

“The term ‘illegal’ feels not accurate to students because it seems to imply that their entire being is illegal, rather than something about how they entered, or a decision their family made that they had no control over,” said Katharine Gin, founder of Educators for Fair Consideration.

“Undocumented” is also inaccurate to describe everyone: it implies that people never had documents, which is untrue, especially of people who came to the U.S. on a short-term visa.

The Applied Research Center and Colorlines.com began a Drop the I-Word campaign in September 2010 as part of a way to humanize a large and diverse group of people. The campaign has other suggested terms, such as “unauthorized.” For now, the DREAM Act movement has embraced the “undocumented” term as part of its identity.

Do Undocumented APIs Have More Options Than Latinos?

Perhaps part of the reason why Asians have been slower to embrace their identity as undocumented is because they didn’t associate with the movement in its early days. “They felt like the term ‘undocumented’ only referred to Mexicans,” said Katharine Gin, founder of Educators for Fair Consideration. Many Asians who are here without legal status originally came over on a visa, and overstayed their visas, versus crossing a border. In Korean and Chinese language media, for example, these are called “overstayers.”

There is also a stigma about talking about family issues, and one’s status could be cause for shame. Some families became undocumented also because of marital status and economic woes, such as Ju Hong’s mother. Their family business went bankrupt around the same time she and her husband separated. Hong’s mother moved to the US, bringing her two children, to start a new life.

Another theory as to why some Asians may be less outspoken is due to the fact that APIs may actually have one more way to change their status: through marriage. Unlike those who come to the US illegally — through crossing a border, for example — those who are here on an expired visa can adjust their status to a green card holder (i.e., permanent resident) more easily by marrying a citizen. People who were never authorized to be in the US cannot marry a citizen and become “legal” without first leaving the country.

“There are a lot of people in the Asian community that are legalized that way and never talk about the fact that they were not here legally at some point,” Gin said. Visa overstayers may also not identify with being “undocumented” because technically, they have documentation, albeit expired.

Regardless of their differences, University of San Francisco law professor Bill Ong Hing points out that while Latinos are the focus of anti-immigrant sentiment today, not too long ago Asian immigrants were the victims of similar vilification. He compares the anti-Asian hysteria from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement (limiting Japanese immigrants, in the face of wide anti-Japanese sentiment in California) to the current anti-Latino and -immigrant climate. “When you read what was written and said about Asians at the time, it’s very hateful,” he said. “Racial and economic competition-wise, it’s exactly the same language as the anti-immigrant rhetoric that happens today.”

Comments