This year marks the 20th birthday of Seeds from a Silent Tree, the first anthology by Korean American adoptee poets, which was published in 1997. Within a decade of its release, poetry collections written by Korean adoptees emerged, including Lee Herrick’s This Many Miles from Desire, Sun Yung Shin’s Skirt Full of Black and Jennifer Kwon Dobbs’ Paper Pavilion in 2007. Nicky Sa-eun Schildkraut’s Magnetic Refrain in 2013 followed, and Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello won the 2015 AWP Donald Hall Prize for Poetry with her collection Hour of the Ox. Now Tiana Nobile has recently published a chapbook, The Spirit of the Staircase, and received a major award from the Rona Jaffe Foundation, an organization that supports women writers in the early stages of their careers.

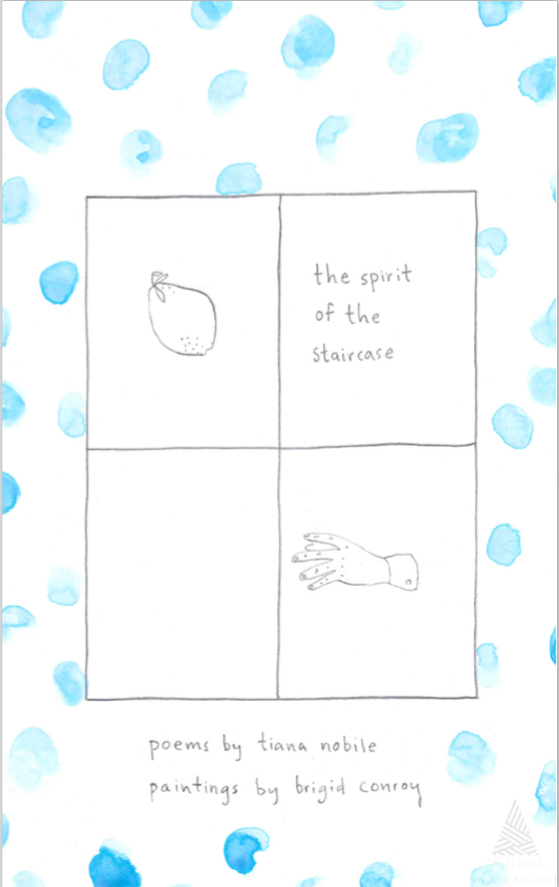

Nobile collaborated on The Spirit of the Staircase with Brigid Conroy, a writer and interdisciplinary artist whose sketches and watercolors appear throughout the book. The collection was published by Antenna, an art and writing collective based in New Orleans, LA, where Nobile currently lives and works as an arts coach and teaching artist at an arts education nonprofit called KID smART. Nobile draws the book’s title from the French phrase, l’esprit de l’escalier, which originally appeared in Enlightenment writer and philosopher Denis Diderot’s Paradoxe sur le comédien. The phrase “refers to the feeling you get when someone says something to you and you think of the perfect response or comeback 20 minutes later as you’re walking away down the stairs,” Nobile says.

The poems in the chapbook grew from a list of invasive and sometimes threatening comments she received from strangers that ranged from “Where are you really from?” and “Go back to China” to “Is it true that Asian Pussies are Sideways?” Sometimes, she said, people would follow her down the street and shout at her when she refused to answer.

“Because my body / is a body / I learn to yield,” the speaker says on the first page. Although Nobile felt as if she didn't have an appropriate response in the moment, she logged the comments in a running list she kept on her iPhone. Writing the poems that would become The Spirit of the Staircase became her way of responding to those people who rendered her “utterly silent, whether it [was] out of fear or pain or just surprise or shock,” she says. “Having been put into this position so many times I finally felt like I needed to take some agency back.”

Nobile intersperses this archive of comments with poems that suggest confinement and resulting helplessness:

Throughout the collection, we continue to see how the speaker struggles to respond to these strangers — which at times results in sublimating her anxiety into feeling as if she is a ghost or collecting her hair as it falls out and hiding it under the rug: “My scalp offers each black /strand of hair as a white flag.”

Nobile grew up in Massapequa Park, a predominately white town on Long Island, NY, and says that she struggled, on one hand, with the burden of being perceived as different from her surrounding community, and on the other hand, with the privilege she inherited from her white, middle-class parents: “I had a comfortable childhood, I went to private schools, I got a really great education.” Sometimes she even daydreamed about what it would be like if she were her parents’ biological child, even though she knew that such a thing would be impossible: “I’m not this mind that can be deposited into a white body [...] my entire life would be different.”

“I would be very open about the fact that I was adopted and it’s kind of impossible not to, if your parents are white,” she says. “But then be like, ‘Oh no, I don’t care’ or ‘it’s not a big deal’ or ‘I have no interest in ever meeting my birth family or ever going to Korea.’ I think I distanced myself so far mentally and emotionally and in the rhetoric I would use with people,” she says.

Attending college at Sarah Lawrence, Nobile says, was an intensely radicalizing and politicizing experience as she began to meet other Asian American people and people of color, and through those relationships, began to articulate the tensions she felt about her identity. She felt further empowered to explore questions of adoption, race and identity through participating in the Kundiman community and recently, through her work while at the Master of Fine Arts program at Warren Wilson College, which included completing her first full-length manuscript, Harlow’s Monkey. Nobile drew the title of the collection from her research on the American psychologist Harry Harlow’s 1950s experiments with rhesus monkeys on maternal deprivation and separation anxiety and their impacts on children’s socio-emotional development. Using Harlow’s experiments as a jumping-off point, Nobile also explores the development of transnational adoption in the context of Operation Babylift during the Vietnam War, which she learned about while watching a documentary about the children who were airlifted out of Saigon and adopted in the United States and other countries.

“Many of those children were not in fact orphans,” she says. “American troops and missionaries went in and just started scooping children off the streets whether or not they were coming from an orphanage or on their way home — that was unknown. There was even footage of some missionaries trying to convince reluctant mothers to give up their children in order to offer them a ‘better life.’ [I]n writing my manuscript I was interested in diving into trying to understand the intersections of those stories and what they reveal about the disempowerment of marginalized women and children who don’t have the resources or the ability to advocate for themselves and how they’re taken advantage of by governments and/or militaries who purposefully sever these relationships and these lineages,” she says.

Within the context of this manuscript, Nobile says, research and found texts both offered points of departure into the writing of the poems as well as connections to other voices that have experienced silencing or erasure. Following influences such as Philip Metres’ Sand Opera that utilizes text from interviews with Abu Ghraib detainees and Srikanth Reddy’s Voyager, which comprises three different erasures of a memoir by former Austrian president and Nazi SS officer Kurt Waldheim, Nobile doesn’t stop at pure erasure. Instead, she writes into the blank spaces she creates. Her poems also fill in missing information in her adoption file, which she recently rediscovered, and which led her to realize that she had not been born in Seoul, as she had initially thought, but in Daejon, a city near the center of Korea. She also discovered that she had been abandoned immediately after her birth; her biological mother was a college student who hadn’t known she was pregnant and who cared for Nobile for a few days in her dorm room before giving her up for adoption. The names of her birth parents were blocked out on the document, but when held to the light, Nobile says, she could still read what was written there. She hasn’t determined what she will do personally with this newfound information, but exploring these documents within her poetry, she says, is a way of reclaiming her agency and provides a means to “create a space of [her] own” within the context of her adoption.

In her creative process, Nobile says she is often interested in repurposing found texts not only “in the way that it destabilizes the original but also engineers a new narrative” — and how such an act can uncover a “submerged narrative from within the original text.”

Despite the geographically expansive reach of her manuscript and about writing about her adoption, Nobile says, she noticed that Korea itself “is markedly absent” from the poems in her collection. In light of this, Nobile plans to use the Rona Jaffe award to return to South Korea for the first time since her adoption at 6 months old.

“[I]t just feels like the logical next step for me personally and creatively to go there because I’ve been writing around this place for so long through writing about my identity and through writing about personal history and adoption, but I have no living memory of that place,” she says.

The last of the strangers’ comments to appear in The Spirit of the Staircase is, “What are you?” to which the speaker responds with images of igneous rocks that are “formed by fire” and “conceived in the belly of a volcano.” The speaker then goes on to trace the rock’s continuous breaking down, re-formation and transformation through weathering, heat and compression. Like the rock, the speaker says, “My body is a stone constantly changing.” The speaker then goes on to wonder if she will “tumble, end-/lessly moving, endlessly seeking / a place to rest [her] head?” The book concludes in uncertainty, but it is no longer the kind of uncertainty that yields to surrender. Instead, Nobile actively converts the spaces created by loss into sites of possibility upon which to foster an identity that is her own, even as it remains in a state of continual adaptation and transformation. Nobile’s work promises to resonate not only within the adopted community but also with others who have experienced different kinds of displacement and trauma — those who, like the speaker in The Spirit of the Staircase, may just be beginning to find their own voices after years of silence.

Comments