In the 1970s, playwright Frank Chin ignited a major controversy in Asian American literature. Responding to the success of Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior, he decried it as “another in a long line of Chinkie autobiographies by Pocahontas yellows blowing the same old mixed up East/West soul struggle.” He argued that the popularity of writers like Kingston and Amy Tan in the mainstream literary market stems from the fact that these “white-washed” Asian American authors pander to white readers by writing autobiographically, which white readers are primed to enjoy because autobiography is a Christian genre “descended from confession.”

Chin’s critique rendered him a contentious figure in Asian American literary circles. Critics found fault with his policing of “real” and “fake” Asian American writers and his masculinized position on what constitutes Asian American authenticity. And yet, I found myself returning to his observation about the omnipresence of traces of the autobiographical in Asian American literature recently, given the spate of texts that have risen to bestseller charts and inundated my bookstagram: E. J. Koh’s The Magical Language of Others, Ly Tran’s House of Sticks, Qian Julie Wang’s Beautiful Country and, of course, Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H Mart.

Two recent additions to this cluster of writings are Kat Chow's memoir, Seeing Ghosts, and Pik-Shuen Fung’s Ghost Forest, a novel which includes autobiographical elements: according to interviews with The Rumpus and Shondaland, Fung grew up in a Chinese Canadian astronaut family, is an artist, and wrote the first vignettes of the novel after her father's death when she was in art school. Both works narrate the loss of a parent and its aftermath. There is much to admire in each. Ghost Forest unfolds in a series of vignettes set in China, Canada and the United States. It centers on an unnamed woman who moved from Hong Kong to Canada at a young age with her mother and grandparents while her father stayed behind in Hong Kong to work. The vignettes in the novel weave oral histories from her grandmother and mother with the narrator’s account of her complicated relationship with her father and the decline of his health. The prose is minimalist but evocative, not unlike the Chinese ink (or xieyi) paintings that the novel references at one point. Fung’s training as an artist is evident in the text. The experience of reading the novel is like walking through an art museum; each vignette is connected, but not necessarily sequential to the vignettes adjacent to it. The result is a series of affective impressions that capture not only the nostalgia and grief attendant to the death of a loved one but also unexpected moments of familial whimsy and humor.

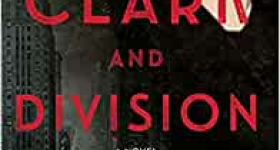

Seeing Ghosts also grapples with grief as it unfurls in a series of short chapters and sections that trace the declining health of Chow’s mother and the family’s attempt — and at moments, failure — to grapple with her eventual death. Interspersed throughout this central narrative are stories of Chow’s extended family’s immigration to Cuba and the United States as well as journalistic snippets on subjects ranging from Yung Wing, the first Chinese immigrant to graduate from Yale, to the tomb of Lon Dorsa, a young man who was killed by a lightning strike in 1897. The result is a rich set of reflections on mortality and Chinese American immigration.

Both Ghost Forest and Seeing Ghosts could be aptly described as haunted (the fact that “ghost” appears in the titles of both books is a giveaway). “Ghost Forest” refers to the protagonist’s eponymous painting, selected for an international student exhibition at the China Academy of Art when she is studying abroad in Hangzhou. Thrilled, she takes her father to see the exhibit as a surprise. But his response is jarring. “I think there is something wrong with you that you’re making art like this,” he says, and then walks away. This scene creates a tension that haunts the rest of the novel — a pain that lingers as the narrator attempts to care for her deteriorating father. Early on in Seeing Ghosts, Chow introduces the morbid motif of her taxidermic mother. This startling image is derived from a joke her mother once made about wanting to be taxidermied when she dies: “So I can sit in your apartment and watch you all the time.” At various points in the memoir, Chow slips into direct addresses to her mother. The effect is that of a haunting presence throughout the memoir. Her mother, taxidermied, watches on as Chow narrates the aftermath of her death.

At another point in the memoir, Chow discovers a striped bass that her father attempted to taxidermy in his basement after a fishing trip. “The fish was positioned on a small table on top of two wooden planks that served as a makeshift stand,” she writes. “Its eyes were congealed, its scales peeling and fins flaky as though it had been deep fried or dipped in Elmer’s glue.” A couple of pages later, she relates an earlier incident when she found in her father’s oven a tray of pet angelfish that he had baked in order to preserve. These scenes culminate in an elegant meditation on the melancholy of “poor taxidermy,” and provide the context for the book’s eye-catching cover. The section is beautifully written. But as I turned these pages, I wondered whose story this was to tell. Was it Chow’s, or was it her father’s? I felt an urge to take the fish gently from the narrator’s hands, put them back in her father’s basement and close the door behind us. Maybe it’s best to let half-taxidermied fish lie.

The literal motif of taxidermy is subtly echoed by the fact that these works are both more or less autobiographical; as a result, every character — including the narrators themselves — are specters of their real-life counterparts on these pages. In a brilliant review of Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise, Katy Waldman observes that writing fiction is about giving life as well as dealing death: “When an author plants a made-up character in a novel, that character gains breath, agency, life. But when an author plants a real person in a novel, she metes out a kind of death.” She adds, “Reading lightly autobiographical fiction … becomes a matter of parsing degrees of realness. It’s sticking your hands through ghosts.” Waldman’s essay attends to fiction, but its observations are thrown into even starker relief in the memoir. With this in mind, perhaps the narrator’s father in Ghost Forest and the narrator’s mother in Seeing Ghosts are not the only ones who haunt these narratives. In these texts, we are walking through ghost forests seeing ghosts.

I relished the poignant prose and insights about family, love and loss in Ghost Forest and Seeing Ghosts. But there were moments when I wanted to protect the characters in these books, when I wanted to unlearn things that I’ve been told about various family members. At one point in Ghost Forest, the narrator recounts a trip to the beach when her father said, “You’d look better if your face were thinner … And if you were two inches taller.” I winced at the way that a white reader might read this. I grew up in Taiwan, where my family traded comments on appearances frankly between passing steaming plates of dongpo pork and stir-fried watercress. Sometimes my westernized sensibilities would chafe at these comments, but most times I just rolled my eyes and dished out my own flippant retorts. But I don’t tell my white friends about these moments. There is something ineffable about these conversations around the slowly rotating lazy Susan that I’m not sure I can — nor want to — capture and reproduce.

The desire for authenticity in Asian American literature is itself an illusory idea because it assumes that authenticity exists in the first place.

Fung and Chow are aware of the dangers of these familial tropes. In their depictions of the narrators’ mothers and grandmothers, they include details that clearly seek to challenge tropes of Asian women as submissive and reserved. In Ghost Forest, the narrator’s grandmother writes and plays the lead in a one-act Cantonese opera. In Seeing Ghosts, Chow describes a goofy face that her mother used to put on where she would “spread [her] lips wide into a grin and [jut] out [her] top front teeth.” But even in these moments, I could not help but regard these characters in relation to the tropes Fung and Chow hope to overcome. This is the reality of the cultural script I have absorbed in the seven years I have lived in the United States.

Unlike Frank Chin, I have no interest in demarcating what is or isn’t authentic Asian American literature. The desire for authenticity in Asian American literature is itself an illusory idea because it assumes that authenticity exists in the first place. This desire belies the fact that authenticity is foreclosed for us — nonwhite writers and readers in majority-white spaces — because we are always already, well, a little bit white: we inevitably see the world through lenses tinted by whiteness. As Brandon Taylor succinctly puts it, there is a “tiny white man” inside each of us. The point is not that Asian American autobiographical writing is “for white people.” Asian American readers will likely enjoy the sophisticated writing and tender reflections offered in Ghost Forest and Seeing Ghosts. I certainly did. The point is that when Asian American writers tell stories about their loved ones, their loved ones not only become ghosts on the page but specifically ghosts defined in relation to a structure of tropes and anti-tropes. Tropes of inscrutable, blunt and/or disappointed Asian elders abound because they — to some extent — comport with reality. But when Asian American writers intentionally or unintentionally slip their loved ones into these tropes by writing them into characters for the eyes of those they will never meet, something a little tragic happens. And considering that tragedy, we might pause to grieve what is lost when those we love become ghosts on the page.

Comments