Editor's Note: The following essay contains a racial slur in the context of a historical quote from a Black soldier. At the request of the author and our belief that the context of the usage is important in this case, we have left the slur as was written in the original text. The piece also contains a graphic image from war. Please be advised.

Tell my friends that I am just the same as a Filipino.

— Ed Brown, 24th Infantry, Buffalo Soldier

The Ones Who Bow Their Heads

I bought a framed print of the Buffalo Soldiers — segregated regiments of African American soldiers originally formed in 1866. The print actually has two images, a photo and its duplicate side by side, meant to be seen through a binocular device in “stereo.” The public domain photo features a perpendicular formation of men in field service apparel, the fat chevrons of the platoon leaders pointing downward on their arms. Their campaign hats give the illusion of a straight line. One of the leaders is framed far left. He faces the camera. The expression of each soldier is serious but calm — power, discipline, unity. The deviations in the formation are inconsequential until you take a closer look and notice a couple of the men’s heads are slightly bowed, breaking the uniformity of the row. Their figures cut a sloping horizon against the top of the frame. Actually, now that I look at it, almost half the photo is sky. A caption, inked in hand, reads: “The 24th U.S. Infantry at drill, Camp Walker, Philippine Islands.” It was taken in 1902.

I’ve carried the photo with me through three cities and half a dozen apartments. It sits in a room in our house for artmaking and workouts as well as meals and the frequent spontaneous dance party. I look at the picture every day. I’m reminded not just of the 24th Infantry pictured but also of the 25th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalries, which served the U.S. military in the wars against Native Americans, the Spanish American War and the Philippine American War.

The Least Reward

If you listen to the vast majority of American school lessons, you would never guess that the Philippines was one of the central subjects of American business and politics during the first decades of the 20th century; in economic terms, sugar — a global commodity that could and would be produced by the islands and Filipino labor then — was tantamount to oil now. The national debate around imperialism included a heated feud among legislators, the press and public about war crimes, when American forces were accused of waterboarding Filipinos. (After over a hundred years, this is still an issue — in 2018 during the U.S. war with Iraq, ProPublica reported that the CIA was still using this torture, this time in Thailand.)

The conflict was so difficult and prolonged, it forced the United States to rethink military practices and weapons. Filipinos — who fought with a hodgepodge of 19th century Spanish muzzleloaders, improvised German Mausers, as well as sticks and knives — were such tenacious warriors that the American military started to reconsider its .38 caliber sidearms, prompting the invention of the Colt .45. One could argue that the conflict even contributed to the rise of the popularity of American football. After the violence in the islands started to wane, the gridiron was where young men could prove their “martial spirit” and so began to channel much of their battlefield fervor to the football field [Tommy R. Thompson, "John D. Brady, the Philippine-American War, and the Martial Spirit in Late 19th Century America," Nebraska History 84 (2003)].

‘Why does the American negro come … to fight us when we are much a friend to him and have not done anything to him. He is all the same as me and me all the same as you. Why don’t you fight those people in America who burn Negroes, that make a beast of you…?’

Many people still believe the American invasion of the Philippines in 1898 was part of the Spanish American War. However, the Filipinos had essentially defanged the Spanish well before the Americans even arrived. That naval skirmish in Manila Bay between Admiral Dewey and the ineffectual Spanish fleet — often regarded as a decisive U.S. victory over the Spanish depicting Americans as saviors — was no more than a scripted, innocuous scene (See Luis Francia’s History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos).

The United States paid Spain $20 million for the islands at the Treaty of Paris, told the world it had a moral obligation to redeem the uncivilized Filipinos (despite steady and significant Westernization since the 16th century) and then conveyed tens of thousands of troops to take the islands over. The conflict would claim the lives of 20,000 Filipino combatants, by some accounts, but 100,000 to 200,000 Filipinos lives were lost as a result of hunger, disease and a general lack of care. Historians would call it an insurrection of Filipinos, but by definition a people can’t insurrect against a foreign power.

This was a war of a sovereign republic against an invading nation — the United States of America. America wanted the land and resources. They wanted Filipino labor. And they sent Black soldiers to do the dirtiest work for the least reward.

Those People Make a Beast of You

When I first ordered the photo of the 24th Infantry, I wanted desperately to make heroes of these Black soldiers, fighters on many fronts, taking up arms on behalf of America as well as fighting to prove their own worth. What could be more heroic than that?

In reality, these Black soldiers were deployed in the islands to fulfill an American imperialist project. They took an oath to fight — and kill — Filipinos who stood in the way of that project. For the Negro soldier, their valiant performance in battle was meant to prove their rightful claim in a country where they were viciously disenfranchised, tortured and killed based on the color of their skin. It took me a little while to fully understand I’d been making heroes of soldiers whose assignment was to subjugate Filipinos by military violence. African Americans explicitly assented to and participated in the murder of my (very recent) ancestors and their countrymen.

My great-uncles were sentenced to be “hanged by the neck until dead” by one of many dubious military tribunals (Hearings Before the Committee on the Philippines of the U.S. Senate, Part 2, pp 1155-1157) . They were accused of wanton murder — Prudencio, Mamerto and Nicasio Llanes. The Senate document cites them as members of the santadahan, Filipino guerillas assembled for the purpose of expelling America and its forces. They were my grandmother’s first cousins; reading the case summary and sentence was the first time I had ever seen any of our family’s history appear in the U.S. official record.

I don’t think it’s an extravagant claim to say that they were murdered for their dissent. American governance accompanied the soldiers, artillery and guns to the islands. Throughout the war, America would take on a range of convenient roles: victim and savior, judge and jury. With an all-white military court whose larger purpose was the acquisition of a group of Pacific Islands, one has to intellectually and spiritually challenge the validity of such a “legal system.” If the United States had any notions of establishing an American democracy in the tropics, it would be accomplished with a Springfield pointed between the Filipino’s eyes.

“The whites have begun to establish their diabolical race hatred in all its home rancor in Manila, even endeavoring to propagate the phobia among the Spaniards and Filipinos so as to be sure of the foundation of their supremacy when the civil rule that must necessarily follow the present military regime, is established,” wrote Sgt. Major John W. Galloway of the 24th Infantry to the Richmond Planet on Dec. 30, 1899. (See Willard B. Gatewood's Smoked Yankees, p. 252)

The Black press did not have foreign correspondents, but they published the letters of Negro soldiers reporting on their experiences in the islands. Numerous missives indicate that the Black soldier swiftly recognized how the color line was being duplicated in the archipelago — this time to include Filipinos. One Black soldier, William Simms, wrote home in 1901: “I was struck by a question a little [Filipino] boy ask me, which ran about this way: ‘Why does the American negro come … to fight us when we are much a friend to him and have not done anything to him. He is all the same as me and me all the same as you. Why don’t you fight those people in America who burn Negroes, that make a beast of you…?’” (Gatewood, p. 237)

The Filipino — evidenced by the nearly quarter million dead as a result of the U.S. invasion — was expendable. In the aftermath of the Battle of Balanggiga, one of the worst losses for the United States, General Jacob H. Smith ordered the slaughter of every Filipino “over the age of ten.” He wanted to turn the land into “a howling wilderness." American soldiers plundered churches and homes. They burned down villages. Many Filipinos were forced into “zones of protection,” which were internment camps intended to prevent guerilla recruitment. Thousands of Filipinos perished from hunger and disease like dysentery.

But the idea of debt and allyship as transaction gives me pause. We become part of the problem when we reduce a Black man to a small subset of actions.

It was the Black soldier who wrestled mightily with the idea of expendability of their foe, for it mirrored their own status in Jim Crow regions of the United States.

Sgt. Patrick Mason, Co. I, 24th Infantry wrote, “I feel sorry for these people and all that have come under the control of the United States. I don’t believe they will be justly dealt by. The first thing in the morning is the ‘Nigger’ and the last thing at night is the ‘Nigger.’ You have no idea the way these people are treated by the Americans here.” (Gatewood, p. 257)

White soldiers were directed by their superiors to stop using the slur to refer to the islanders because their Black counterparts were starting to identify with the Filipinos. According to historian Willard B. Gatewood, the word nonetheless reverberated among white soldiers throughout the conflict, a brazen refrain that followed the Black soldiers from the U.S. mainland across an ocean. The Jim Crow line would be inscribed in a land halfway around the globe. In words and deeds, the white military made it clear that Black soldiers should expect the same inhuman status they were forced into in the American South. And in the islands, they would be joined by the Filipinos.

Sgt. Major Galloway, who would eventually be disciplined for suspected collaboration with the Filipinos, succinctly predicted the fate of the islanders: “The future of the Filipino, I fear, is that of the Negro in the South.” (Gatewood, p. 253)

For some members of the Black military, this was more than enough motivation to defect. The most famous among them was a man named David Fagen.

Reimagining Fagen

Lately, David Fagen’s name has been circulating on the internet, especially widely in Filipino American social media networks. What you will find out is that Fagen lived in Tampa, where he enlisted in the 24th Infantry on June 4, 1898. He shipped off to Manila and soon ran into conflict with his superiors. Fagen defected to the Filipino side on November 17, 1899, when he slipped away on a horse provided by the Filipinos, with whom he must have already had contact. (For a brilliant account of Fagen’s life, read Rene Ontal’s “Fagen and Other Ghosts” in Vestiges of War, edited by Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis Francia.)

Fagen would fight alongside the guerilla resistance and eventually rise to the rank of Captain, leading Filipinos into battle against the Americans numerous times over a period of two years. His most famous feat was the capture of a supply barge, enabling the Filipinos to take a valued haul in guns and ammo.

Colonel Frederick Funston became obsessed with Fagen’s capture, offering a bounty for his head. One American came to hunt the Black officer down, but never found him. Fagen’s saga was chronicled all over America’s newspapers at the time, and he became so renowned that a bike thief took on his name.

U.S. military records contend that a Filipino showed up at an American encampment asking to collect bounty for the killing of the deserted Black soldier. He handed the Americans a sack with a slightly decomposed head that he said was Fagen’s. According to the official U.S. account, the former infantryman was positively identified. This was enough for the Americans to officially declare Fagen dead, though various alternative theories about his escape and survival have been offered.

Fagen is the principal figure cited in social media in urging Filipinos to support the Black Lives Matter movement, a kind of Filipino debt to African Americans. But the idea of debt and allyship as transaction gives me pause. We become part of the problem when we reduce a Black man to a small subset of actions. A story that claims Filipinos owe African Americans requires a heroic salvation narrative. It also undermines a story of two peoples' subversion of systemic racism by mutual recognition. We owe it to ourselves and African American history to imagine a more complete David Fagen.

But where did Edison find Filipinos to play the vanquished enemy? Well, he didn’t. Edison had the white guardsmen play the American soldiers. He had Black men play the Filipinos.

For example, stop for a moment to think about Fagen’s first weeks among Filipinos. What language did he speak to his new comrades and what language did they speak to him? It’s very possible he spoke with them in Spanish, as many soldiers — Black and white — had some facility with Spanish words and phrases. But isn’t it highly likely, after so much close contact with the Filipinos, that they taught Fagen some Tagalog, possibly Ilokano? And isn’t it likely that he taught the Filipinos some (or a lot of) English? If he did, then surely it was a version of Southern Black English.

If you’ve ever traveled or studied a foreign language, then you know this awkwardness, this richness, this traveling away from one’s self. You know the painful fumbles and you know the exhilaration of connection. Do we imagine these soldiers never had to grieve one of their fallen? To comfort one another? To gather like that? To think together? To quarrel? To pray? Do we dare imagine they did not eat and drink and laugh together? Was there no time for the Filipinos to point to a bright bird circling or a spectacular reptile sunning on a rock? Was there no urge to notice the very land they were fighting for? No compulsion to share the gorgeousness of the local?

In my mind, Fagen’s story doesn’t reveal a man whose questions are solely about the acquisition of power and fame. He strikes me as a figure who passionately wanted to be his own uncompromised self, who understood that all the estimations America had made of him — no matter how widely broadcast or brutally enforced — were rank failures. He strikes me as one who not only saw the brutal injustice against Filipinos but how it resonated with the life of the Negro in America. Is it not feasible that Fagen was continually teaching and embodying qualities of Blackness that Filipinos — over 300 hundred years of Spanish colonization — had been conditioned to be ashamed of? Isn’t it equally feasible that the Fiilpinos — who had sustained an effective armed resistance to expel a European oppressor — embodied qualities Fagen only dreamed of or could not see under the watch of whiteness?

Fagen not only must have relished being accepted by the Filipinos, his acceptance of them also must have been the source of incredible challenges and countless instances of affection. (I’m hearing Cesaire’s moving lines, “J’accept … J’accept … entiérement, sans réserve. …”) His formal role among Filipinos was that of soldier and finally officer. But it is the informal, the spontaneous, the seemingly miniscule gesture — down to our breathing — that gives shape to our lives.

If there is a debt owed to Fagen, especially one that persists into the 21st century, it must be accounted for in light of the days, hours and minutes these men lived and fought among one another — not just the heroic, but the mundane, which especially in a time of crisis and violence is the very substance of beauty.

I say, Fagen was beloved. And I say he loved the Filipino back.

Edison’s Dream

During the first year of the American occupation of the archipelago, the new technologies of silent film gave rise to hundreds of moving pictures for public consumption in America and Europe. One of them, titled “Filipinos Retreat from the Trenches,” was produced in June 1899, just a couple weeks before David Fagen and the 24th and 25th Infantries departed California for the Pacific.

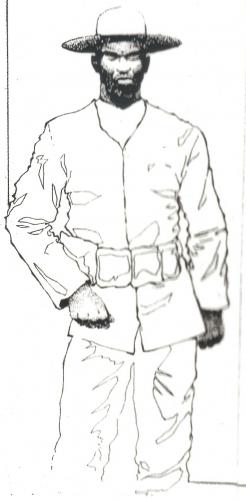

The movie camera shows us Filipino soldiers shooting from a standing position in a deep trench. Dressed in all white — or what looks like white in the film’s monochrome — the men are turned mostly away. We can’t see the details of their dark faces. They are pointing their Mausers at something off screen.

To me, they are beautiful, the line and muscle of each torso defined by sashes fitted at the waists of their uniforms. They’re dressed so fine that for a second, I think they should be heading out for a long night of body rock at the club. But this is 1899. Though the bullets are invisible, smoke zips from their muzzles then billows into loaf-sized clouds, a larger fog now, a host of indistinguishable ghosts, reversing into the trench where the lean barrels rise, then drop between firing.

The soldier in the foreground partially hides the fighter next to him. He seems to relax as he reaches into his back pocket for another cartridge, a rural casualness. Even when they’re firing their weapons, they shift their easy weight with little tension in their hips. The gun kicks, knocking back the front foot of the soldier standing closest to us.

Look now how the second closest man to the camera gets one shot off before he falls to his back knee, then drops. And his two comrades in the background crumple face down as another pair breaks to escape. The Filipino soldier closest to us bounds out of the picture. The smoke has gloomed the far half of the trench, and I can make out two or three other heads turning to flee.

I grew up in Edison, N.J., a town named after the man who produced this film. And that man, Thomas Alva Edison, was an imperialist.

As an adolescent, I used to ride my bike past his labs, a landmark now, where he developed the light bulb. For decades, I had no clue about his association with Filipino history — that is, my history. Among the gadgets to come out of those labs was a sound machine called the phonograph, tech ancestor to the turntable, which my friends and I joyfully pried open, disassembled, and remade as a DJ crew, rocking hundreds of ’80s and ’90s dance floors — an important site of friendship, sexual discovery, love and rivalry for our generation. (Note: See Christine Balance’s book, Tropical Renditions) That is to say, we reinvented Edison’s invention. We broke the rules of the machine by breaking the machine itself and putting it back together better than it was received. And then we danced to the tool of our remaking.

Not 13 seconds into Edison’s movie, along the left edge, a flag appears. Even from the old film stock restored in 1996 and digitized, we can quickly make out the stars and stripes. A soldier in dark uniform entering from the left and gripping the flagpole is white. A squadron of Americans, also white, follows him into the shot. For a second, it looks like the standard bearer might plant the pole into the back of one of the dead. The American fighters, having taken the trench, open fire in the direction of the retreated Filipinos now off screen. And the flag man steps over the neck of his enemy.

Edison moved his labs up a ways to West Orange, N.J. And there in the hills of Essex County, in 1899, he directed this battle between Americans and Filipinos.

The Library of Congress credits the New Jersey National Guard as the actors. I think to myself, that explains the white American soldiers who charge and win the trench. But where did Edison find Filipinos to play the vanquished enemy? Well, he didn’t. Edison had the white guardsmen play the American soldiers. He had Black men play the Filipinos.

In the midst of systemic violence, abuse and manipulation, our shared story offers an alternative historical model where whiteness, white governance, white institutions do not mediate how we interact.

I watch the film over and over. When the Black actors run, Filipinos run. When the Black men shoot at the oncoming charge of white soldiers, Filipinos are shooting too. When the bodies fall, they are Filipino and they are Black at the same time.

The final image of the film is a mounted sergeant or officer slowing his horse, which is losing its footing on the slope, so that the animal is about to slide into the ditch. One of the Filipinos, lying down as if he’s already been shot, suddenly stands up, afraid of being trampled under hoof — not as an act but in fear for his actual safety and real life. The Black actor recovers his role, staggers a few steps and dies again in a safe distance from the beast. The horseman fires his sidearm toward the heavens. In the foreground lie four corpses. There are no more living Filipinos in the frame. The film ends.

The minute-long clip means to be an allegory of the fight between good and evil, between the civilized and the savage in the Philippine Islands. But the movie unwittingly reveals the cardinal fancy of white supremacy.

When Edison’s white soldiers move, they are moving the front line. This line has already traveled with them halfway around the world. It is their most prized cargo. The line stands for American Imperialism. The line stands for Jim Crow. The line stands for both at the same time. Plessy v. Ferguson effectively declared war on Black folks. By violence, by the gun and by the noose, that 10,000 mile line was meant to be enforced. The line, as W.E.B. Du Bois famously put it, is the problem of the 20th century, “the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.”

Sometimes the American dream of the line is that the enemy can’t cross it. So America moves the line with a flag. They move the line with guns. Whiteness dreams of moving the line until there is no space on the other side. They dream of moving the line until there are no people on the other side. As the line moves, the functional area of whiteness grows. It is Edenic actually. Whiteness dreams of a world without the line. The future of the Black world is the future of the line. The future of the line is its obsolescence. Its obsolescence depends on the extinction of the people on the other side.

Before the end of the movie, the flag exits the frame. The guns keep following. The white soldiers who bear the line of battle and the line of American imperialism and the line of Jim Crow chase down the soldiers — who are Black, who are Filipino, who have run to avoid dying at the line. This side of the world is now white. And there is no other side of the world.

Forget that Filipinos fought guerilla style; forget they didn’t follow the convention of the line. To the Filipino there were no lines. There was only the land. And the land — hills, rivers, flora — was their collaborator. In a time before Europeans, in a time before white people in the islands, in a time before the idea of whiteness, the land and trees were holy, the fruits of those trees holy, the water holy and the wind and breath itself holy. Filipinos listened to the land. They shouted their names into forests. (My family still does this.) They grieved with the land. They asked permission from the land. They took care of the land as the land took care of them. During the war with the Americans, the Filipinos read the land and saw no lines. But Americans inscribed a line into the land. The line was an illusion. There was only the land. The Filipinos weren’t crossing a line. They were living.

To understand the scale of the fantasy so clearly designed in Edison’s movie, one must see it as the predecessor for The Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith’s epic lie which would be produced a decade and a half later and become a rallying document for white supremacy and the Klan.

But one must also think about African American film history, how Edison’s production featuring Black actors was released little more than a year after the recently recovered 19th century film short Something Good – Negro Kiss, which featured early Black entertainers Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown kissing and exchanging affections. Furthermore, Edison’s film came 15 years before the work of the great Black auteur Oscar Micheaux.

I want to remake the Edison film. I want to visit those hills of West Orange. Maybe somewhere along I-280, there’s a green and brown mound and a ditch where Edison’s cameraman dropped his tripod. And maybe Edison is still there shouting at the Black men and white men to get into position. Maybe there, where they loaded their guns. Blanks.

Let’s do it again. Let’s call the descendants of the Black men who played the Filipinos in the film. Let’s invite them to the site of the production. Let's kick Edison off the set. Let’s talk about what three or four generations of America looks like. Let’s gather. It's time to retell the 20th century.

How to Make a People Disappear

I’m writing this in the middle of outrage and mourning. I’m writing this to try and figure out how I came to my own anger and my own sorrow about Black folks harassed, assaulted and murdered without accountability from white people and the police that defends them. I’m writing this from a space of Asian America, a space that is meant to be vast and inclusive, but one that I have often felt excluded from. I’m writing this from a space of sadness and isolation, from a premonition that we are being pulled apart from one another, an uncomfortable hunch that we are weakening.

This history of oppression — which is really a history of Black-Filipino resistance, Black-Filipino improvisation, Black-Filipino intimacy and Black-Filipino mutual regard — has all but disappeared from our national consciousness. I would argue, this disappearance is a fundamental part of our shared pain.

White supremacy counts on us being busied with addressing the white center, making it damn near impossible for us to witness each others' histories and lives. But mutual regard makes us incredibly strong. What would it mean to remember together even as we can and must remember apart?

The American imperialist era in the Philippines aligns squarely with the years between Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and the beginning of the Great Migration (c. 1920). Keith Green, my colleague who is a scholar of African American captivity, told me that for a long time this period was referred to as The Nadir. The era was considered a kind of void in the story of Black people in the United States and so had gone mostly unexamined.

The launch of this plan for white dominance set off a unique relationship between African Americans and Filipinos. (See Nerissa Balce’s “Filipino Bodies, Lynching, and the Language of Empire” in Positively No Filipinos Allowed: Building Communities and Discourse, edited by Antonio Tiongson et al.). Not only did each of our peoples resist this horrific blueprint, we constructed resistance in tandem. This cooperation was the genesis of mutual regard, in which these two peoples of color beheld each other without the mitigation of whiteness. In the midst of systemic violence, abuse and manipulation, our shared story offers an alternative historical model where whiteness, white governance, white institutions do not mediate how we interact.

I believe our Black-Filipino history, which is to say our many affinities and exchanges, were erased because this mutual acknowledgment was a threat to the dream of white mastery. At the turn of the century, we were hyperpresent with one another; within a decade, we were apparently hyperinvisible to one another. In short, American government, education and industry collectively shaped a story that erased Black-Filipino connections for virtually the whole 20th century.

But they couldn’t douse the fire of collaborative resistance completely.

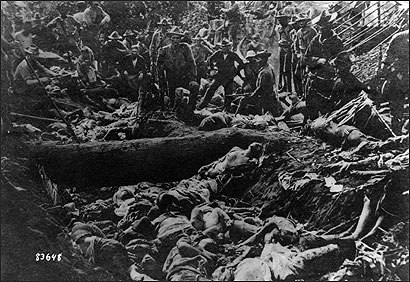

Du Bois’ invocation of Asia and the Pacific Islands in the struggle against the oppressive color line wasn’t mere rhetoric. In 1906, he was horrified by the slaughter of some thousand Filipinos in the Southern region of the islands. A famous photo of that massacre at Bud Dajo showed American soldiers standing over a ditch full of Filipino corpses. Incidentally, the picture is a grotesque and eerie antecedent to the photos of Abu Ghraib. Du Bois thought the picture of American atrocity should be enlarged, duplicated and distributed to Black folks throughout the United States to expose the brutality of American conquest.

Du Bois also exchanged letters with Black educators in the archipelago, sensing an opportunity for more African American teachers in the Philippines. In fact, one of the first Black Americans to teach in the islands was a young man named Carter G. Woodson, who would spend his formative years in the tropics, then return to America and chronicle his observations of racist pedagogy in the United States in a seminal book called The Mis-Education of the Negro. As you probably know, his passionate critique of the white education system in the U.S. mainland — which he documented in the Philippines, too — led to the establishment of Black History Month.

One of the most significant Black Filipino exchanges in the decades between the World Wars is also often the most overlooked. During my research, I stumbled across a telegram from the Workers’ Peasants Defense Society of the Philippines to the governor of Alabama dated May 12, 1932: “PHILIPPINE MASSES PROTEST AGAINST UNCHRISTIAN UNCIVILIZED INHUMAN SCOTTSBORO BOYS EXECUTION DEMAND THEIR IMMEDIATE RELEASE.” The Scottsboro Boys were nine African Americans, from 12 to 19 years old, falsely accused of raping two white women on a train. All served prison time. They were eventually pardoned — posthumously, in 2013.

It's true that the Scottsboro case drew international attention with the boys receiving vocal support from the Communist party around the world. Nonetheless, the Workers’ Peasants Defense Society is worth noting because this demand was sent barely two years after Filipino laborer Fermin Tobera was shot and killed in his sleep in Watsonville, California.

Filipino laborers were the objects of scorn for stealing the jobs of white Americans. But the more severe offense that caused race riots up and down the West Coast was that Filipinos — affectionately known to each other as manongs — danced with white women.

A labor organizer from Yakima, in a presentation to the Congressional Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, summarizes white anxiety around the presence of Filipinos on the U.S. mainland: “Let it be remembered that most of these Filipinos are musicians, and that the character of their music is of the sentimental and appealing (to passions sort), and that the Filipinos dress flashily, spend their money lavishly on the girls, and Chief Mann [of Toppenish, Wash.] said: ‘They are just as dangerous when allowed free social contact with women as that of the negro when given the same liberty.’”

The same labor organizer continues: “One of the prominent men in Toppenish, with whom I talked yesterday, said: ‘If I had my way, I would declare an open season on all Filipinos and there would be no bag limit.”

Those hearings were prompted in large part by the riots in Watsonville, which resulted in numerous assaults on Filipinos by white posses, in addition to the lynching of Fermin Tobera. The violence erupted after white Watsonville residents were horrified by a picture in the local newspaper of a manong, Perfecto Bandalan, with his white bride-to-be Esther Schmick. The outrage and fear of the sexual threat of Filipinos escalated to such a degree that the United States decided to deal with the “Filipino problem” by first offering to repatriate the brown-skinned laborers and then ultimately granting the islands their independence.

The United States was not a magnanimous steward of the lowly Filipino. There was no American moral awakening that led to Philippine independence. Americans abused, murdered and finally ejected the very people they brought in to do the jobs they wouldn’t do. White Americans were terrified of the miscegenation of Filipino men and white women. Though the fused line of imperialism and Jim Crow no longer materialized on the battlefield, the vile racialization of Filipinos continued well into their migration to the mainland.

Quotas imposed by the Tydings McDuffie Act in 1934 essentially prohibited the immigration of Filipinos. Eventually, under different circumstances, Filipinos and Black folks would be reintroduced because of the Pacific theater in World War II. And in 1963, two years before Filipinos would finally be permitted to immigrate to the United States again, James Baldwin would publish A Fire Next Time, his shining document of love and anger. Baldwin’s book has become canonical in racial discourse, but few readers seem to notice the epigraph that follows his loving letter to his nephew and precedes the iconic, raucous, prayerful meditation on Black faith, family and survival. The epigraph is from a poem titled “White Man’s Burden” by Rudyard Kipling.

This poem has a specific history. It was written in reference to the ostensible responsibility of white men to lift Filipinos out of their savagery.

Is it possible that a writer as thoughtful as James Baldwin did not know the time and historical circumstances of the white poet’s work? It seems unlikely to be a casual gesture. It seems more likely that Baldwin recognized the specific, joined legacy between Jim Crow and imperialist white supremacy in the Philippines.

Asian guilt is a fear that you’ll be found out as one of the bad guys. Asian guilt is internalized white guilt. Ironically, it is another kind of assimilation.

Two years ago, I gave an informal lunch presentation organized by our students. I offered them bits and pieces of the many artifacts and documents from Filipino American history that I’d uncovered over the years. I thought aloud about the racialization of Filipinos from Alaska to Southern California and the terrifying resemblance of that racialization to other ethnic minorities, not the least of which were African Americans.

After the talk, I went back to my apartment and I got a text from Shawn Jones, a Black poet in the program who was at the gathering: “So recently, my cousin sent me this picture of my great-grandfather. It is the only picture we have of him.”

I looked at the black and white photo of a man with a high forehead and square chin. He was slim. His skin was light brown. His shoulders were slightly forward, and I could almost see the beginning of a smile. He was handsome.

She continued, “My cousin said his mother was Filipino.”

Shawn — a grandmother herself — had no idea of her Filipino ancestry. She didn’t have a historical context to even understand that was possible. My talk was the first she had heard of the Philippine American War and the involvement of African American soldiers. She was a descendant of our shared history.

How many more African American families can trace their story to the Buffalo Soldiers of the Philippines? In the public eye, in my lifetime, I think of Nate Robinson, whom I loved during his tenure with the Knicks. And as a writer, how can I not acknowledge Jayne Cortez, whose life in the Black Arts Movement included poetry but also the music of the Black Avant Garde?

White supremacy rewards us — as it did in the Philippines — for making all-or-nothing foes of one another. White supremacy counts on us being busied with addressing the white center, making it damn near impossible for us to witness each others' histories and lives. But mutual regard makes us incredibly strong. What would it mean to remember together even as we can and must remember apart? Remembering in communion expands our inner lives, the richness of our solitude. It is a practice of shared joy, shared sorrow, shared outrage, shared feeling.

I am afraid that we have been missing from each other for a long time.

A Spiritual Dimension of Justice

When there is racial conflict in the United States, it is almost always framed in literally black and white terms. Asian Americans are forced into a strange and awful deliberation. America has so deeply conditioned the immigrant and his descendants with fear that he quietly wants to know how to make himself safe. He will side with whoever is most powerful.

In my mind, instead of picking a side, we should be moved toward a profound moral and historical questioning.

Asian guilt is a fear that you’ll be found out as one of the bad guys. Asian guilt is internalized white guilt. Ironically, it is another kind of assimilation. A commitment to justice for Black lives is not predicated on a confession of one’s wrongs to Black people. A commitment to justice is predicated on a conscience. Self-indictment is not a conscience. Blame is not a conscience. Neither is debt evidence of a conscience. Reflection, inquiry, a reimagining of the self, especially in relation to other folks — that is the beginning of love. And love is at the center of all justice.

Furthermore, Asian guilt is built on a monolithic Asian identity and doesn’t take into account specific historical Filipino-Black intersections. No other Asian country was ever fully subject to the U.S. fantasy of Jim Crow like the Philippines. And still, our mutual regard is not limited to our suffering: Our modes of mourning and celebrating and gathering, our improvisations with the land and local material, our disobedience in and against a master language are highly legible to one another. Our creolizations, our tricksterisms, our interrogation of the world with the body, if we take care to look, are mutually intelligible.

Kinship as story — as question, as seeing — I didn’t invent it. It is in our epistolary literature and newspapers. it is in our photos and film history. It is greater than solidarity. And it is radically different from the popularized narrative of debt. Mutual regard is a social dimension of resistance. It is a spiritual dimension of justice itself.

As a writer, I feel a strong identification with the Black soldiers who wrote home to chronicle — and even reimagine — their own lives while they were in the Pacific. They recorded the Philippines and Filipinos not as entirely separate, but as related, connected, even the “same.” What they found were intimacies — and kinships, too. In my work as an artist, I record my life, and I record Black life, because it is — and has always been right in front of me. Black life is in the history that made me. It is in the history that made my parents and grandparents and great grandparents. We — Filipinos and Black folks — are in each others’ trauma, but we are also in each others’ dreams, wishes, deep memory and imagination.

This is the 21st century. The enmity is here. The intimacies and kinships are so powerfully here. Regardless.

This essay is for Remi, Milo, and Kalesi, for Uma, Nina, and Arima, for Alem and Ezmi, for Jason, for the Invencion kids and the Triunfante kids, for Jackie’s unborn child, for Dazz's kids, for Naomi Reid, for Sasha and Mikaela Rose, for all the Calulo kids, for all the Malamug kids, for all the Douge kids, for our history, for our dreaming, for the love that made you, for the love you make.

***

For a brief list of resources for a mutual regard, see here.

Comments